Georgia Tech-Lorraine

In 1843, archaeologists excavated the burial grounds of Remiremont Abbey in Lorraine, France (the abbey was founded in the 7th century). It was medieval custom to bury the deceased with cross-shaped plaques cut from thin sheets of lead placed across the chest. The crosses often included inscribed prayers, but many of those inscriptions have been rendered unreadable over the ensuing centuries by layers of corrosion. Now, an interdisciplinary team of scientists has successfully subjected one such funerary cross to terahertz (THz) imaging and revealed its hidden inscription—fragments of the Lord’s Prayer (Pater Noster)—according to a new paper published in the journal Scientific Reports.

“Our approach enabled us to read a text that was hidden beneath corrosion, perhaps for hundreds of years,” said co-author Alexandre Locquet of Georgia Tech-Lorraine in Metz, France. “Clearly, approaches that access such information without damaging the object are of great interest to archaeologists.” According to the authors, this approach is also useful for studying historical paintings, detecting skin cancer, measuring the thickness of automotive paints, and making sure turbine blade coatings adhere properly.

In recent years, a variety of cutting-edge non-destructive imaging methods have proved to be a boon to art conservationists and archaeologists alike. Each technique has its advantages and disadvantages. For instance, ground-penetrating radar (radio waves) is great for locating buried artifacts, among other uses, while lidar is useful for creating high-resolution maps of surface terrain. Infrared reflectography is well-suited to certain artworks whose materials contain pigments that reflect a lot of infrared light. Ultraviolet light is ideal for identifying varnishes and detecting any retouching that was done with white pigments containing zinc and titanium, although UV light doesn’t penetrate paint layers.

There are also many X-ray imaging technologies that have been used to reveal new details about artifacts, including a famous 1788 portrait of Antoine Lavoisier and his wife by the Neoclassical painter Jaques-Louis David; the hull of Henry VIII’s favorite warship, the Mary Rose, which sank in battle in 1545; the 14th-century tomb of Edward of Woodstock (aka the Black Prince); and the mysterious Antikythera mechanism, an ancient device believed to have been used to track the heavens.

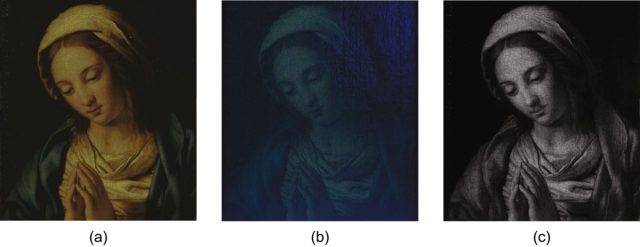

Junliang Dong et al., 2017

THz imaging fills a critical gap in frequencies ranging from about 100 GHz to 10 THz, according to co-author David Citrin of Georgia Tech. The technique gives researchers the ability to image a large object quickly and cheaply extract useful information about that object. Even better, THz radiation can penetrate paints and glazes without damaging the objects being imaged.

Citrin has compared the technique to how seismologists identify various layers of rock in the ground by emitting pulses of sound and then measuring the returning echoes. THz imaging uses high-frequency pulses of electromagnetic radiation in much the same way, measuring how that terahertz radiation reflects off the various layers of paint.

This latest project builds on Citrin’s 2017 work applying terahertz scanners and data processing to examine the layers of a 17th-century painting: the Madonna in Preghiera, attributed to the workshop of Giovanni Battista Salvi da Sassoferrato. The painting was placed face-down, and the scanner emitted pulses of THz radiation every 200 microns across the canvas, measuring the reflections to discern layers between 100 to 150 microns thick.