The US has now identified 45 monkeypox cases scattered across 15 states and the District of Columbia, while the multinational outbreak has reached more than 1,300 confirmed cases from at least 31 countries. No deaths have been reported.

In a press briefing Friday, US health officials provided updates on efforts to halt the spread of the virus and dispel unfounded concerns that the virus is spreading through the air.

To date, no cases of airborne transmission have been reported in the outbreak, which has almost entirely been found spreading through sexual networks of men who have sex with men. Monkeypox may spread through large, short-range respiratory droplets, and health care providers are encouraged to mask and take other precautions during specific procedures, such as intubation. But the general potential for spread via smaller, long-range aerosols is more speculative and theoretical.

“Monkeypox is not thought to linger in the air and is not typically transmitted during short periods of shared airspace,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Rochelle Walensky said in the briefing. There’s no evidence to suggest its spreading by having a casual conversation, passing someone in a store, or touching the same item, such as a doorknob, she noted.

Officials are seeing that the current outbreak is spreading through “close, sustained physical contact,” she added. “This is consistent with what we’ve seen in prior outbreaks and what we know from decades of studying this virus and closely related viruses.”

The CDC is still collecting clinical data on some of the country’s 45 cases, but of those with data, all are related to direct physical contact, such as sex, CDC officials said. Most are linked to international travel.

“Everyone reports a type of close contact that can be associated with direct, skin-on-skin contact,” Jennifer McQuiston, deputy director of CDC’s Division of High Consequence Pathogens and Pathology, said in the briefing. “It’s often difficult to separate out what a face-to-face [respiratory] droplet transmission might look like compared to direct skin-on-skin contact because people are very intimate and close with one another. But all of our patients have reported direct skin-on-skin contact.”

Officials were eager to clarify the points after The New York Times ran a controversial story earlier this week emphasizing the potential for airborne transmission while drawing comparisons to communication failures earlier in the COVID-19 pandemic. Virologists and health experts have already noted that evidence of airborne transmission for monkeypox is thin at best—and clearly not the primary mode of transmission. The article also can increase stigma around the infection, some said, which health authorities have been working hard to avoid.

Real concerns

Moreover, as Walensky noted, unlike the novel coronavirus, which public health officials and virologists scrambled to understand during the mushrooming pandemic, experts have decades of experience with monkeypox. The virus was first identified in monkeys in 1958, and the first human case was seen in 1970. There have been periodic outbreaks in Central and West Africa, where the virus is endemic and exists in animals. For instance, separate from the multinational outbreak, there have been more than 1,400 confirmed and suspected cases in endemic countries this year, including 66 deaths.

While airborne transmission is not a significant concern, health officials are racing to contain the current outbreak and urging people to take it seriously. Earlier this week, the World Health Organization called on countries to “make every effort to identify all cases and contacts to control this outbreak and prevent onward spread.”

“The risk of monkeypox becoming established in non-endemic countries is real,” WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said.

While the outbreak continues to largely be seen in men and, specifically, men who have sex with men, the virus can spread to and infect anyone. There have already been a small number of cases identified in women. “WHO is particularly concerned about the risks of this virus for vulnerable groups, including children and pregnant women,” Tedros said.

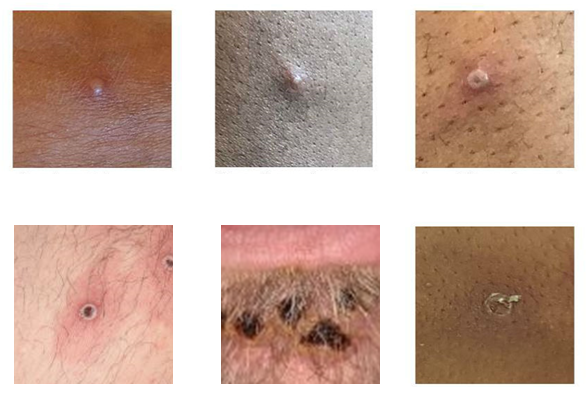

In Friday’s briefing, Walensky and other federal health officials highlighted some of their work to contain the outbreak. That starts with efforts to raise awareness about the disease and what it looks and feels like. Cases can’t be tested, treated, or traced unless people know what to look for.

In this outbreak, monkeypox appears to be mainly presenting—but not entirely—as it has in the past: an illness developing five to 21 days after prolonged physical contact with an infected person. Usually, monkeypox begins as a flu-like illness before progressing to include a telltale rash with lesions all over the body, concentrating on the extremities, including the face, palms of the hands, and soles of the feet. The lesions begin as flat but then become raised, filled with fluid, and scab over. The lesions contain large numbers of the virus, and direct contact with them, their fluid, or materials contaminated by the lesions, is how the virus spreads. A person is thought to be no longer contagious when all lesion scabs fall off, and a fresh layer of intact skin has formed.