Researchers in the United Kingdom have come up with the most detailed, complex hypothesis yet to explain the burst of mysterious cases of liver inflammation—aka hepatitis—in young children, which has troubled medical experts worldwide for several months.

The cases first came to light in April, when doctors noted an unusual cluster of hepatitis cases in young children in Scotland. The illnesses were not linked to any known cause of hepatitis, such as hepatitis (A to E) viruses, making them unexplained. Though unexplained cases of pediatric hepatitis arise from time to time, a report that month noted 13 cases in Scotland in two months when the country would typically see fewer than four in a year.

Since then, the World Health Organization has tallied more than 1,000 probable cases from 35 countries. Of those cases, 46 required liver transplants, and 22 died. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified 355 cases in the US. As of June 22, 20 US cases required liver transplants, and 11 died.

Hypotheses to explain the cases have been wide-ranging. Some have suggested—particularly adamantly—that the cases may be aftereffects of an infection with the pandemic coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2. The CDC, meanwhile, published data that found there hasn’t been an increase in pediatric hepatitis cases or liver transplants over pre-pandemic baseline levels, which suggested the unusual clusters may not represent a new phenomenon.

Combination of factors

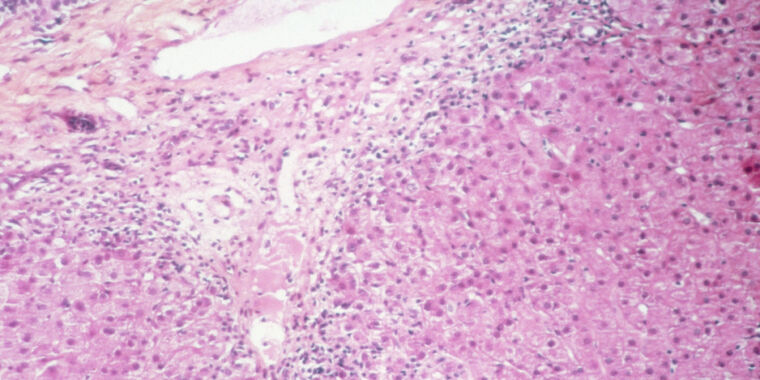

But a common feature among the cases has been an infection with an adenovirus. The extremely common childhood viruses have shown up in many cases. As such, many hypotheses have involved adenoviruses, but this, too, is puzzling, because adenoviruses are not known to cause hepatitis in previously healthy children.

In two new reports, UK researchers offer a fresh hypothesis that may be the clearest but most complex explanation. Their data suggests that the cases may arise from a co-infection of two different viruses—one of which could be an adenovirus and the other a hitchhiking virus—in children who also happen to have a specific genetic predisposition to hepatitis.

In one of the new studies, looking at nine early cases in Scotland, researchers found that all nine children were infected with adeno-associated virus 2 (AAV2). This is a small, non-enveloped DNA virus in the Dependoparvovirus genus. It can only replicate in the presence of another virus, often an adenovirus but also some herpesviruses. As such, it tends to travel with adenovirus infections, which spiked in Scotland when the puzzling hepatitis cases arose.

Most striking, while all nine of the hepatitis cluster cases were positive for AAV2, the virus was completely absent in three separate control groups. It was found in zero of 13 age-matched healthy control children; zero of 12 children who had an adenovirus infection but normal liver function; and zero of 33 children hospitalized with hepatitis for other reasons.

This finding was backed up in a separate study led by researchers in London, which looked at 26 unexplained hepatitis cases with 136 controls. It also found AAV2 in many of the hepatitis cases, but in very few of the control cases.

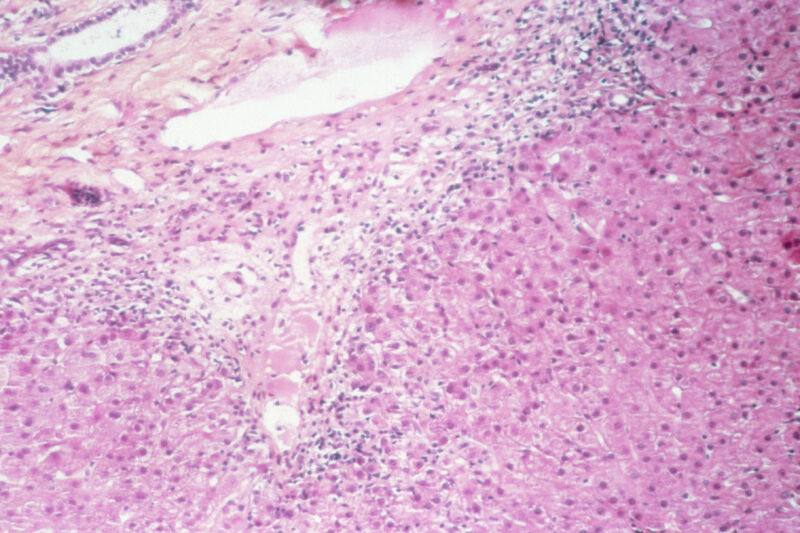

Predisposition

The study of the nine cases in Scotland went a step further by examining the children’s genetics. The researchers noted that eight of the nine children (89 percent) had a gene variant for a human leukocyte antigen called HLA-DRB1*04:01. But this gene variant is only found in about 16 percent of Scottish blood donors, well below the frequency found in the hepatitis cases. Moreover, HLA-DRB1*04:01 is already known to be linked to autoimmune hepatitis and some rheumatoid arthritis cases.

Generally, human leukocyte antigen (HLA), also known as major histocompatibility complex or (MHC), are proteins outside of immune cells that present antigen—such as viral or bacterial peptides—to T cells. This presentation trains the T cells on how to respond to potential threats, triggering immune responses to invading germs or tolerance to specific antigens. Thus, HLA proteins play a critical role in influencing immune responses.

The Scottish study suggests that all three factors combine to explain the hepatitis cases: An adenovirus infection and a tag-along AAV2 infection, one of which triggers an aberrant immune response in children with a genetic predisposition. It’s unclear how all the factors combine exactly, but, based on the nine cases, all three factors are necessary. This could explain why the hepatitis cases are so rare, linked to adenovirus infections, and appeared to cluster after pandemic restrictions were lifted, when many susceptible children became infected with common viruses, including adenoviruses.

Of course, this is just a hypothesis for now—and one mainly based on only nine cases in a study that has yet to be peer-reviewed. Researchers will have to do far more work to determine if this hypothesis explains the cases, including looking at larger cohorts of children and molecular research to understand the potential mechanism.