When Napoleon was infamously defeated at Waterloo in 1815, the conflict left a battlefield littered with thousands of corpses and the inevitable detritus of war. But what happened to all those dead bodies? Only one full skeleton has been found at the site, much to the bewilderment of archaeologists. Contemporary accounts tell of French bodies being burned by local peasants, with other bodies being dumped into mass graves. And some accounts describe how scattered bones were collected and ground up into meal to use as fertilizer.

It’s that last claim that particularly interests Tony Pollard, director of the Center for Battlefield Archaeology at the University of Glasgow. He has examined historical source materials like memoirs and journals of early visitors, as well as artworks, to map the missing grave sites on the Waterloo battlefield in hopes of finding a definitive answer. He recently provided an update on his efforts thus far in a recent paper published in the Journal of Conflict Archaeology.

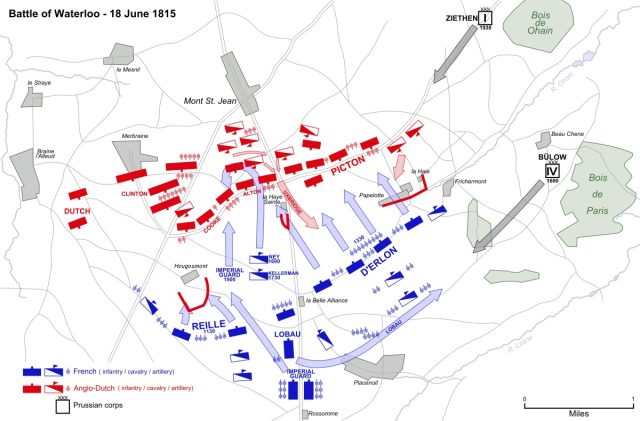

Napoleon had initially been defeated and deposed as emperor of France in 1814, ending up in exile on the island of Elba in the Mediterranean. He briefly returned to power in March 1815 for what is now known as the Hundred Days. Several states opposed to his rule formed the Seventh Coalition, including a British-led multinational army led by the Duke of Wellington and a larger Prussian army under the command of Field Marshal von Blücher. Those were the armies that clashed with Napoleon’s Armée du Nord at Waterloo.

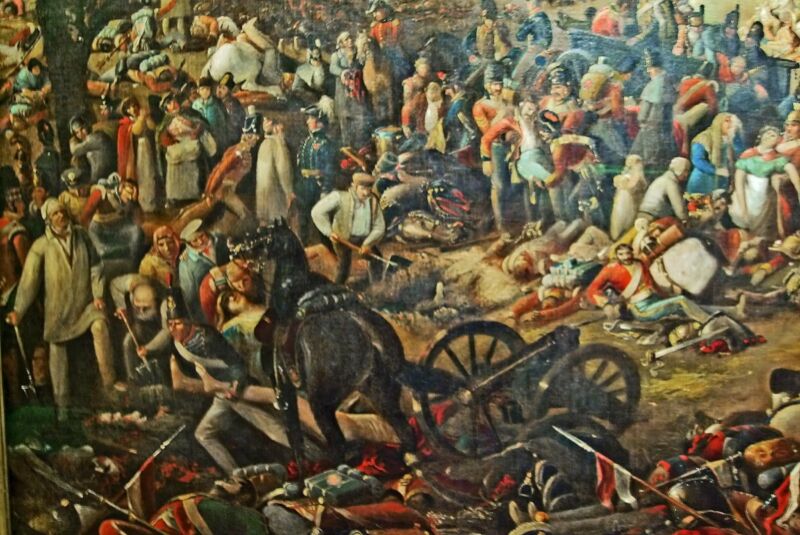

Historians still argue about exactly when the battle began, but Wellington’s dispatches indicate that Napoleon “commenced a furious attack upon our post at Hougoumont” at about 10 am on June 18. This was a large country house partially obscured by trees, one of several key locations on the Waterloo battlefield. The fighting raged for eight hours across multiple sites.

In the end, Wellington’s casualties amounted to some 15,000 dead or wounded, while Blücher’s forces suffered 7,000 dead or wounded. Napoleon’s forces fared worse: between 24,000 and 26,000 men were killed or wounded, including several thousand who were captured. An additional 15,000 French soldiers deserted over the ensuing days.

This made for a monumental clean-up task. One contemporary account, by Major W.E. Frye, described the battlefield on June 22 as “a sight too horrible to behold.” Frye recounted “the multitude of carcasses, the heaps of wounded men with mangled limbs unable to move and perishing from not having their wounds dressed or from hunger.”