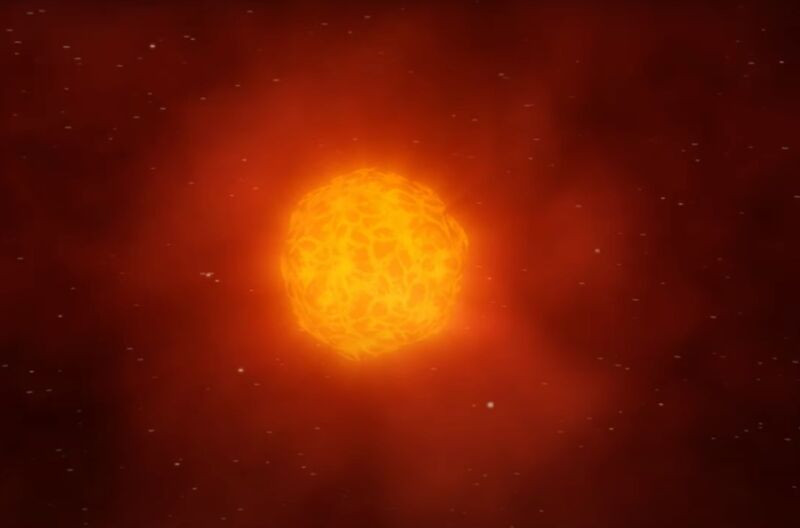

European Southern Observatory

Astronomers are still making new discoveries about the red supergiant star Betelgeuse, which experienced a mysterious “dimming” a few years ago. That dimming was eventually attributed to a cold spot and a stellar “burp” that shrouded the star in interstellar dust. Now, new observations from the Hubble Space Telescope and other observatories have revealed more about the event that preceded the dimming.

It seems Betelgeuse suffered a massive surface mass ejection (SME) event in 2019, blasting off 400 times as much mass as our Sun does during coronal mass ejections (CMEs). The sheer scale of the event is unprecedented and suggests that CMEs and SMEs are distinctly different types of events, according to a new paper posted to the physics arXiv last week. (It has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.)

Betelgeuse is a bright red star in the Orion constellation—one of the closest massive stars to Earth, about 700 light-years away. It’s an old star that has reached the stage where it glows a dull red and expands, with the hot core only having a tenuous gravitational grip on its outer layers. The star has something akin to a heartbeat, albeit an extremely slow and irregular one. Over time, the star cycles through periods when its surface expands and then contracts.

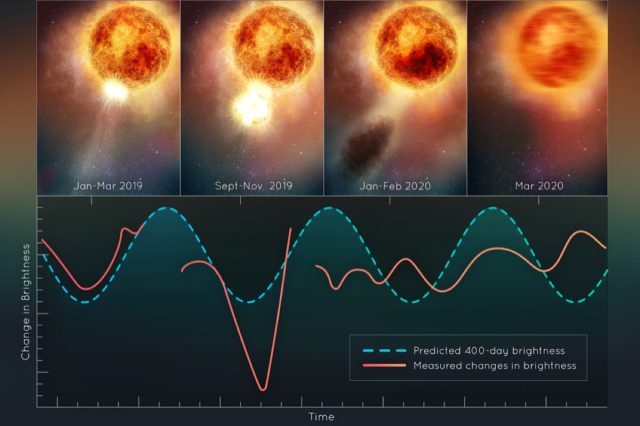

One of these cycles is fairly regular, taking a bit over five years to complete. Layered on that is a shorter, more irregular cycle that takes anywhere from under a year to 1.5 years to complete. While the cycles are easy to track with ground-based telescopes, the shifts don’t cause the sort of radical changes in the star’s light that would account for the changes seen during the dimming event.

As we’ve reported previously, astronomers first noticed the strange, dramatic dimming in the light from Betelgeuse in December 2019. The star dimmed so much that the difference was visible to the naked eye. The dimming persisted, decreasing in brightness by 35 percent in mid-February before brightening again in April 2020.

Astronomers puzzled over the phenomenon and wondered whether it was a sign that the star was about to go supernova. Several months later, they had narrowed the most likely explanations to two: a short-lived cold patch on the star’s southern surface (akin to a sunspot) or a clump of dust making the star seem dimmer to observers on Earth. Last year, astronomers determined that dust was the primary culprit, linked to the brief emergence of a cold spot.

The ESO team concluded that a gas bubble was ejected and pushed further out by the star’s outward pulsation—sort of like a stellar “burp.” When a convection-driven cold patch appeared on the surface, the local temperature decrease was sufficient to condense the heavier elements (like silicon) into solid dust, forming a veil that obscured the star’s brightness in its southern hemisphere.

NASA/ESA/Elizabeth Wheatley (STScI)

According to the authors of this latest paper, the event was significantly more than a mere stellar burp. A large convective plume with a diameter of over 1 million miles bubbled up from deep in the red giant’s interior. The resulting shocks and pulsations were powerful enough to produce an SME, blasting a massive chunk of the star’s photosphere into space. That produced the cold patch covered by the dust cloud, which explains the dimming.

The red giant has only just begun to heal from that catastrophic event. “Betelgeuse continues doing some very unusual things right now; the interior is sort of bouncing,” said co-author Andrea Dupree of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, likening the activity to a plate of Jell-O. Its trademark pulsation has also stopped—hopefully temporarily—perhaps because the interior convection cells “are sloshing around like an imbalanced washing machine tub” as the photosphere begins the slow process of rebuilding itself.

“We’ve never before seen a huge mass ejection of the surface of a star,” said Dupree. “We are left with something going on that we don’t completely understand. It’s a totally new phenomenon that we can observe directly and resolve surface details with Hubble. We’re watching stellar evolution in real time.” The Webb Space Telescope may be able to detect the ejected material in infrared light as it continues moving away from the star, which might tell astronomers even more about what happened—and its implications for other similar stars.

DOI: arXiv, 2022. 10.48550/arXiv.2208.01676 (About DOIs).

Listing image by ESO/P. Kervella/M. Montargès et al.