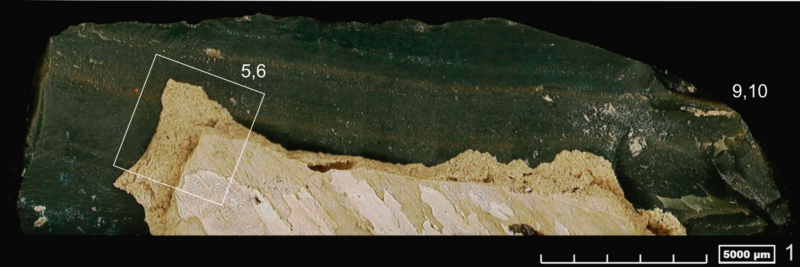

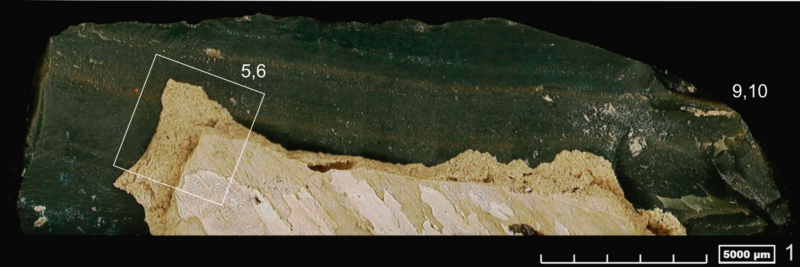

Enlarge / This chert bladelet still has a remnant of its bone haft attached. (credit: Wang et al. 2022)

We know the oldest human cultures only from their most durable parts: mostly stone tools, sometimes bone. Show an experienced Pleistocene archaeologist a chert blade, and they can probably tell you which hominin species made it, how long ago, and where. But the 40,000-year-old stones and bones archaeologist Fa-Gang Wang and his colleagues recently unearthed at a 40,000-year-old Chinese site called Xiamabei look like nothing archaeologists have seen before.

Unique stone tool technology

The people who lived at Xiamabei, in northern China’s Niwehan Basin, used a toolkit that consisted mostly of tiny bladelets (small, sharp pieces of stone), often hafted onto bone handles. Based on microscopic traces of wear and tear on the tools, people at Xiamabei seemed to have used the same generic bladelets for everything from scraping hides and cutting meat to boring wood and whittling softer plant matter.

Nearly every one of the 382 stone tools unearthed at Xiamabei is less than four centimeters long; making and using these smaller blades would have allowed early humans to do more work with less material. Handles helped make the tools easier to grip and more versatile; Wang and his colleagues found one bladelet with part of a bone haft still attached to the stone. On several of the 17 other bladelets the researchers examined closely for microscopic signs of wear, they found tiny scratches left by bone handles, along with imprints from the plant fibers used to bind the bladelets in place.