Public domain

Historians widely consider the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE to be the decisive event that led to Octavian defeating Mark Antony and Cleopatra. The couple committed suicide—Antony by stabbing himself in the stomach, and Cleopatra by the bite of an asp (or, alternatively, by some other poison). Octavian subsequently became the Roman Emperor Augustus, thereby ushering in the Pax Romana, a 200-year period of peace and prosperity that lasted until 180 CE.

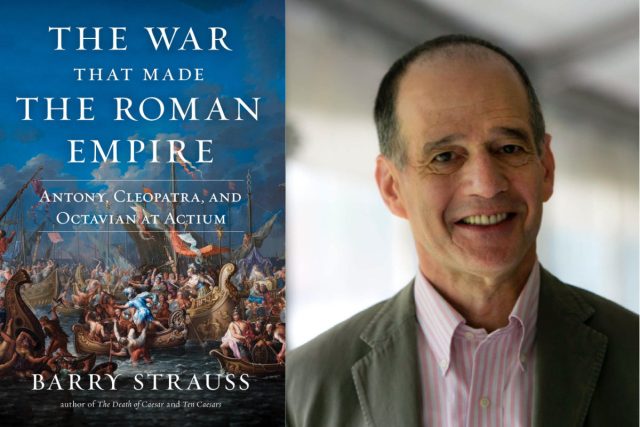

Barry Strauss, a historian at Cornell University, argues that the true pivotal moment in the conflict occurred some six months before as part of a strategic campaign to cut off the supply lines for Antony and Cleopatra’s forces. Strauss makes his case in his new book, The War that Made the Roman Empire: Antony, Cleopatra, and Octavian at Actium, re-creating the battle in detail, as well as what he maintains was the turning point of the war six months before.

This is a particularly dramatic historical period that inspired two separate historical plays by William Shakespeare. Roman general and statesman Julius Caesar was famously stabbed to death at the Curia of Pompey on the ides of March in 44 BCE. The senators who killed him thought assassination was the only way to preserve the republic, but the murder ultimately led to the republic’s collapse. The following year, Caesar’s adopted son, Octavian, formed the Second Triumvirate with Mark Antony and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus.

Alas, the Second Triumvirate proved to be highly unstable, due in large part to the bitter rivalry between Octavian and Antony. Octavian successfully pushed Lepidus into exile in 36 BCE, claiming the latter’s provinces for himself. Meanwhile, Antony married Caesar’s former lover, Cleopatra, queen of Egypt, and sought to dominate Rome from there. Civil war inevitably broke out (the third and last of the Roman Republic), with the young and relatively inexperienced Octavian on one side and Antony and Cleopatra (supported by 40 percent of the Roman Senate) on the other.

Leemage/Corbis/Getty Images

On paper, Antony and Cleopatra seemed assured to win the war, given their combined resources and experience with military strategies and campaigns. Yet Octavian ultimately prevailed. According to Strauss, it was Octavian’s reliance on Roman General Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, who successfully waged a naval campaign to cut off supply lines to Antony’s army, giving Octavian the upper hand. That campaign included the seizure of the city of Methone, a strategically significant port in an obscure corner of southern Greece.

“Actium was a great battle, but it did not stand alone,” Strauss writes in his introduction. “It was the climax of a six-month campaign of engagements on land and sea. Nor were all of the operations military. The war between Antony and Octavian involved diplomacy, information warfare—from propaganda to what we now call fake news—economic and financial competition, as well as all of the human emotions: love, hate, and jealousy, not least among them.”

Ars spoke with Strauss to learn more.

Ars Technica: You specialize in ancient military history, but you seem to have a particular fascination for this moment in Roman history—and especially this particular battle. Why is that?

Barry Strauss: I was incredibly lucky when I was a graduate student. I got to spend a year in Greece with the American School of Classical Studies in Athens. In the fall of 1978, I was taken to Nicopolis by the school. Among the students, there were two people who devoted their lives to studying the site there, Konstantinos Zachos, a Greek archeologist who excavated the site of Augustus’ victory monument, and Bill Murray, a naval archaeologist and naval historian, who measured the size of the rams on the site. They both got me really interested in the subject early on. As for Julius Caesar and Octavian, I’d done a military history of Caesar. So this battle was kind of the missing link between Caesar and Octavian. And of course, there’s Cleopatra, who’s just utterly irresistible.

Simon & Schuster/Barry Strauss

Ars Technica: Literature, particularly Shakespeare’s plays, has colored our perception of many of these figures. One reason is that the source material is notoriously scant. How do you find good reliable sources, especially in cases where you have to reconstruct what happened based on a few lines of text here and there?

Barry Strauss: That’s one of the main things that we as ancient historians do. We have to read against the grain, and we have an adversarial relationship with the sources. So first of all, we have to ask, “Where is each author coming from?” to get a sense of what his biases might be. Then we gather a huge amount of material so that we can fill in the blanks.

A lot of that material is archaeological. A fair amount of it is based on what I might call reconstruction or some knowledge of how the sea works, of how boats work, of how war works. That allows us to narrow things down. Sometimes, honestly, we have to go for competitive plausibility. We can’t always say, “Well, we’re sure this has happened,” but we can say, “We consider this the likeliest reconstruction.” But it’s tough. It’s really difficult stuff.