Liu Míng Sun/EyeEm/Getty Images

There’s rarely time to write about every cool science-y story that comes our way. So this year, we’re once again running a special Twelve Days of Christmas series of posts, highlighting one science story that fell through the cracks in 2022, each day from December 25 through January 5. Today: New analysis of an ancient Chinese text revealed the earliest candidate aurora yet found, predating the next oldest by three centuries.

A pair of researchers has identified the earliest description of a candidate aurora yet found in an ancient Chinese text, according to an April paper published in the journal Advances in Space Research. The authors peg the likely date of the event to either 977 or 957 BCE. The next earliest description of a candidate aurora is found on Assyrian cuneiform tablets dated between 679-655 BCE, three centuries later.

As we’ve reported previously, the spectacular kaleidoscopic effects of the so-called northern lights (or southern lights if they are in the Southern Hemisphere) are the result of charged particles from the Sun being dumped into the Earth’s magnetosphere, where they collide with oxygen and nitrogen molecules—an interaction that excites those molecules and makes them glow. Auroras typically present as shimmering ribbons in the sky, with green, purple, blue, and yellow hues.

There are different kinds of auroral displays, such as “diffuse” auroras (a faint glow near the horizon), rarer “picket fence” and “dune” displays, and “discrete aurora arcs”—the most intense variety, which appear in the sky as shimmering, undulating curtains of light. Discrete aurora arcs can be so bright, it’s possible to read a newspaper by their light. That was the case in August and September 1859, when there was a major geomagnetic storm—aka, the Carrington Event, the largest ever recorded—that produced dazzling auroras visible throughout the US, Europe, Japan, and Australia.

The Bamboo Annals is a chronicle of ancient China, written on bamboo strips, that begins with the age of the Yellow Emperor and runs through the so-called Warring States period (5th century–221 BCE), when rival states were engaged in intense competition. It ended when the state of Qin unified the states. The original text of the Bamboo Annals was buried with King Xiang of Wei, who died in 296 BCE, and wasn’t discovered until 281 CE, thus surviving Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s burning of the books in 212 BCE (not to mention burying hundreds of Confucian scholars alive).

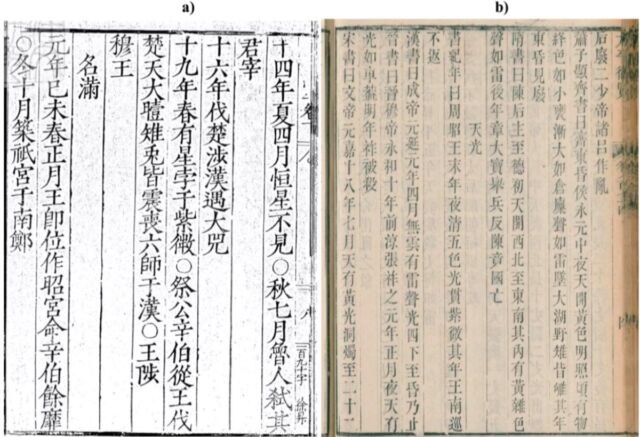

M.A. van der Sluijs & H. Hayakawa, 2022

The original text consisted of 13 scrolls that were lost during the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE). There are two versions of the Bamboo Annals still in existence. One is known as the “current text,” consisting of two scrolls printed in the late 16th century. Many scholars believe this text is a forgery, given the many discrepancies between its text and portions of the original quoted in older books, although some scholars have argued that some parts might be faithful to the original text. The other version is known as the “ancient text,” and was pieced together by studying the aforementioned quoted portions found in older books, especially two dating back to the early 8th century CE.

Independent researcher Marinus Anthony van der Sluijs and Hisashi Hayakawa ofNagoya University relied on the ancient text for their new analysis. This text describes the appearance of a “five-colored light” visible in the northern part of the night sky towards the end of the reign of King Zhao of the Zhou dynasty. Auroras tend to only be visible in polar regions because the particles follow the Earth’s magnetic field lines, which fan out from the vicinity of the poles. But powerful geomagnetic storms can cause the auroral ovals to expand into lower latitudes, often accompanied by multicolored lights. Per the authors, during the 10th century BCE, Earth’s north magnetic pole was about 15 degrees closer to central China than today, so the people there may well have witnessed such displays.

While this is technically an unconfirmed candidate aurora, “The explicit mention of nighttime observation rules out daytime manifestations of atmospheric optics, which sometimes mimic candidate events,” the authors wrote. Furthermore, “The occurrence of a multicolored phenomenon in the northern sky during the nighttime is consistent with visual auroral displays in mid-latitude regions.” According to van der Sluijs and Hayakawa, the 16th century current text’s translation of the passage in question described the event as a “comet,” rather than a “five-colored light,” which is why the candidate aurora has not been identified until now.

DOI: Advances in Space Research, 2022. 10.1016/j.asr.2022.01.010 (About DOIs).