It began decades ago, with a few hardy pioneers slogging north across the tundra. It’s said that one individual walked so far to get there that he rubbed the skin off the underside of his long, flat tail. Today, his kind have homes and colonies scattered throughout the tundra in Alaska and Canada—and their numbers are increasing. Beavers have found their way to the far north.

It’s not yet clear what these new residents mean for the Arctic ecosystem, but concerns are growing, and locals and scientists are paying close attention. Researchers have observed that the dams beavers build accelerate changes already in play due to a warming climate. Indigenous people are worried the dams could pose a threat to the migrations of fish species they depend on.

“Beavers really alter ecosystems,” says Thomas Jung, senior wildlife biologist for Canada’s Yukon government. In fact, their ability to transform landscapes may be second only to that of humans: Before they were nearly extirpated by fur trappers, millions of beavers shaped the flow of North American waters. In temperate regions, beaver dams affect everything from the height of the water table to the kinds of shrubs and trees that grow.

Until a few decades ago, the northern edge of the beaver’s range was defined by boreal forest, because beavers rely on woody plants for food and material to build their dams and lodges. But rapid warming in the Arctic has made the tundra more hospitable to the large rodents: Earlier snowmelt, thawing permafrost and a longer growing season have triggered a boom in shrubby plants like alder and willow that beavers need.

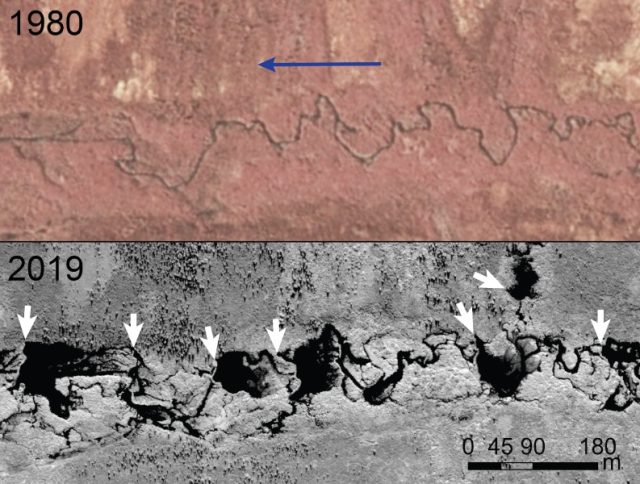

Aerial photography from the 1950s showed no beaver ponds at all in Arctic Alaska. But in a recent study, Ken Tape, an ecologist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, scanned satellite images of nearly every stream, river and lake in the Alaskan tundra and found 11,377 beaver ponds.

Further expansion may be inevitable.

K.D. Tape et al / Scientific Reports 2022

Beaver hotspots

All these new dams could do far more than alter the flow of streams. “We know that beaver dams create warm areas,” Tape explains, “because the water in the ponds they create is deeper and doesn’t freeze all the way to the bottom in the winter.” The warm pond water melts the surrounding permafrost; the thawed ground, in turn, releases long-stored carbon in the form of the greenhouse gases carbon dioxide and methane—contributing to further atmospheric warming.

While changes to the Arctic brought on by warming will happen with or without beavers, the fragility of the far-north ecosystems leaves them especially vulnerable to the kinds of disturbances beavers may cause. In fact, the tundra may be the environment most threatened by climate change on the planet, according to paleobotanist Jennifer McElwain of Trinity College Dublin, author of an article about plant reactions to ancient warming episodes in the Annual Review of Plant Biology.

McElwain and her colleagues examine fossil leaves and use the number and size of pores, or stomata, on the leaves to infer the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere those plants breathed. “When there’s very high carbon dioxide atmospheres, you see plants with bigger and fewer stomata,” she explains. At times when atmospheric CO2 was higher than around 500 ppm, forests grew in the high Arctic.

“During greenhouse intervals in the Earth’s deep past, we have forested ecosystems all the way up to 85, 86 degrees north and south latitude,” McElwain says. There were no places on Earth where the climate was too cold for trees to grow during these times. And where there are trees, the animals that depend on them—such as beavers—can thrive. In fact, there is evidence that a forested Arctic is where the beaver’s dam-building skills first evolved, millions of years ago (see sidebar).

In the past, as now, the polar regions warmed faster than the rest of the planet because heat is carried poleward by the global circulation patterns of the oceans and atmosphere. And since human combustion of fossil fuels has now pushed atmospheric CO2 levels to 415 ppm and climbing, the spread of shrubs and trees onto today’s warming tundra appears unavoidable—as does the spread of animals that need those plants to survive.

Tape has tracked both beavers and other creatures that have moved north onto the tundra in the wake of climate change, including moose that feast on tall, dense growths of shrubs that didn’t exist there 70 years ago. But the impact of beavers on the landscape is unique.

“It’s best to think of beavers as a disturbance,” Tape says. “Their closest analogue is not moose. It’s wildfire.”