Bloomberg | Getty Images

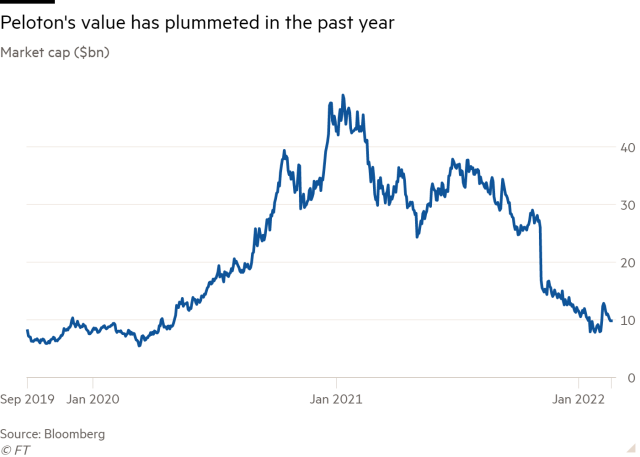

As Peloton’s stock price began to tumble last autumn and just months after a costly recall of the connected fitness company’s expensive treadmills, its executives were confronted with a new crisis.

In September last year, staff at Peloton warehouses, which receive high-end bikes originally manufactured in Taiwan, noticed that paint was flaking off some of the exercise machines.

The cause was a build-up of rust on “non-visible parts” of the bike—the inner frame of the seat and handlebars—and did not affect the product’s integrity, Peloton recently told the Financial Times.

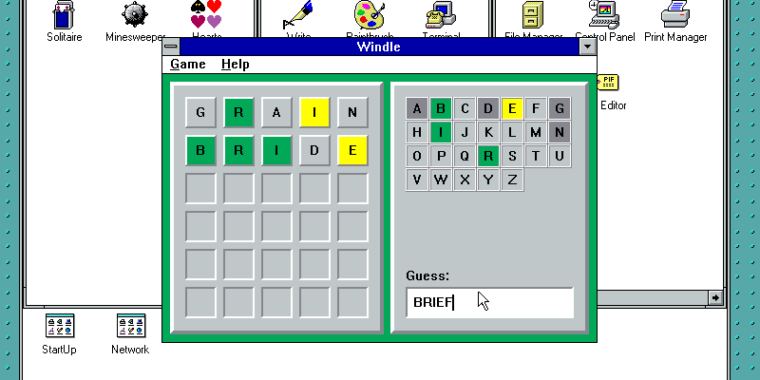

Instead of returning the bikes to the manufacturer, executives hatched a plan, dubbed internally as “Project Tinman,” to conceal the corrosion and sent the machines to customers who had paid between $1,495 and $2,495 to purchase them.

The project was first revealed in FT Magazine last week but eight current and former Peloton employees across four US states have provided further details on the operation.

They described the plan as a nationwide effort to avoid yet another costly recall just months after the company’s most tragic episode—the death of a child due to the design of its treadmill.

Bloomberg | FT

Internal documents seen by the FT showed that Tinman’s “standard operating procedures” were for corrosion to be dealt with using a chemical solution called “rust converter,” which conceals corrosion by reacting “with the rust to form a black layer.” Employees said the scheme was called Tinman to avoid terms such as “rust” that executives decided were out of step with Peloton’s quality brand.

Insiders were also angered about enacting a plan that they argued cut across Peloton’s supposed focus on its users, who are called “members” to evoke a sense that buyers are more than customers and part of a broader community. Tinman also put a spotlight on the company’s quality control process versus meeting aggressive sales targets in the search for growth.

“It was the single driving factor in my beginning stages of hatred for the company that I had spent the previous year and a half falling in love with,” said an outbound team lead, who reviews products before they are shipped to customers.

Peloton said the issue affected at least 6,000 bikes and that 120 staff had undertaken “rigorous testing” on the devices to conclude the rust—which it described as “cosmetic oxidation”—had “no impact on a bike’s performance, quality, durability, reliability, or the overall member experience.”

The US Consumer Product Safety Commission, which oversaw the recall of Peloton’s treadmill, would not say whether it had been alerted to the corrosion issue, but said companies must notify it if they suspect defects “which could create a substantial product hazard or . . . an unreasonable risk of serious injury or death.”

The company is in turmoil, having announced 2,800 job losses this month, with co-founder John Foley stepping aside as chief executive. Peloton plans to cut $800 million from its annual costs.