Getty Images

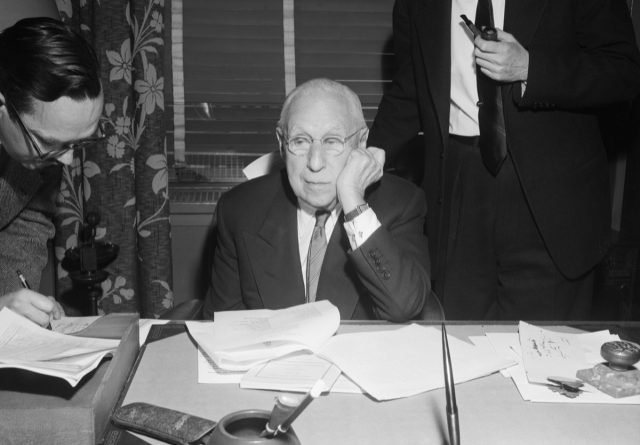

There’s rarely time to write about every cool science-y story that comes our way. So this year, we’re once again running a special Twelve Days of Christmas series of posts, highlighting one science story that fell through the cracks in 2022, each day from December 25 through January 5. Today: The US Secretary of Energy finally nullified the 1954 revocation of J. Robert Oppenheimer’s security clearance, acknowledging that the controversial decision resulted from a “flawed process” that violated its own regulations.

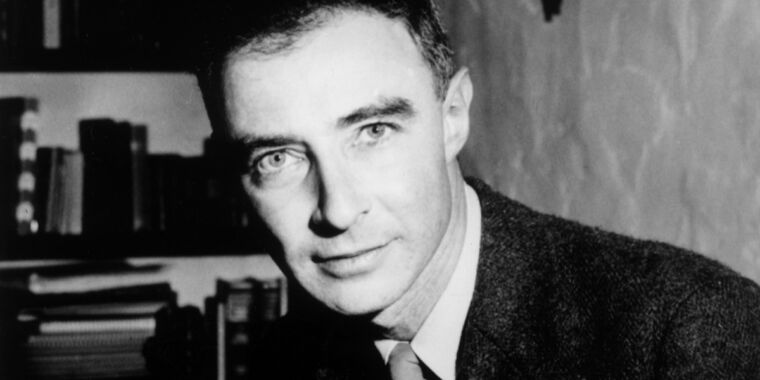

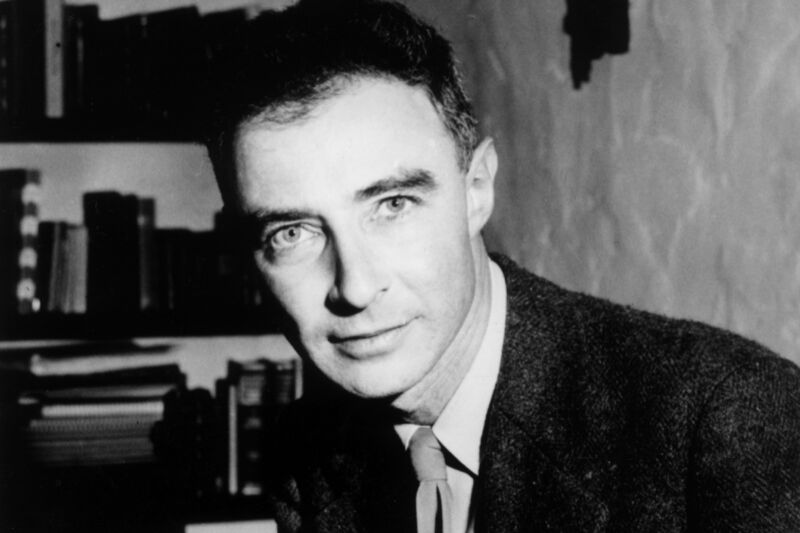

Nearly 70 years after having his security clearance revoked by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) due to suspicion of being a Soviet spy, Manhattan Project physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer has finally received some form of justice just in time for Christmas, according to a December 16 article in the New York Times. US Secretary of Energy Jennifer M. Granholm released a statement nullifying the controversial decision that badly tarnished the late physicist’s reputation, declaring it to be the result of a “flawed process” that violated the AEC’s own regulations.

Science historian Alex Wellerstein of Stevens Institute of Technology told the New York Times that the exoneration was long overdue. “I’m sure it doesn’t go as far as Oppenheimer and his family would have wanted,” he said. “But it goes pretty far. The injustice done to Oppenheimer doesn’t get undone by this. But it’s nice to see some response and reconciliation even if it’s decades too late.”

Oppenheimer was born in New York City to German Jewish immigrants and studied physics under Ernest Rutherford at Cambridge, before earning his PhD from the University of Gottingen in 1927 under Max Born. He eventually joined the faculty at the University of California, Berkeley. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved the Manhattan Project and tapped Major General Leslie R. Groves to head it, Groves in turn chose Oppenheimer to lead the secret weapons laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico. True, Oppenheimer had left-wing political views, and hadn’t won a Nobel Prize (although he was nominated several times). But Groves felt the physicist had the breadth of knowledge to bring together physicists, chemists, engineers, and metallurgists, among other disciplines whose expertise would be crucial to the success of the project.

Getty Images

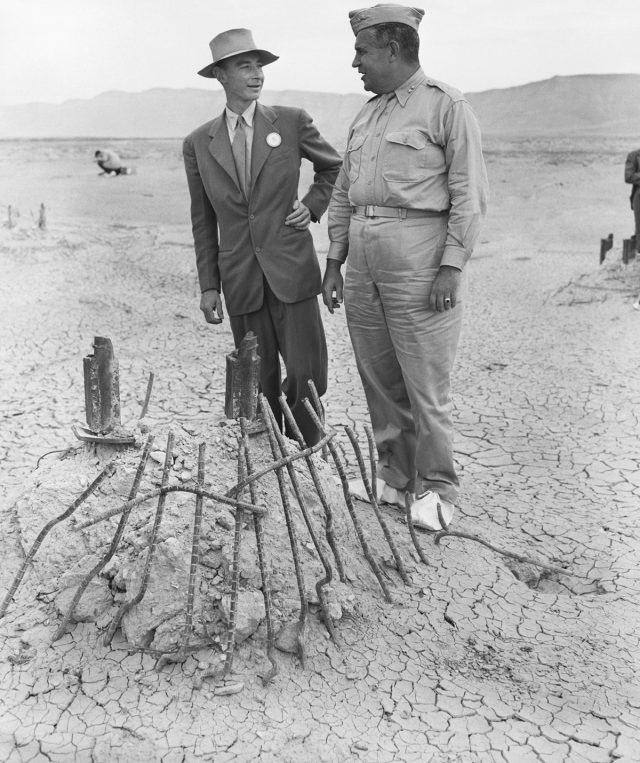

And the project did succeed. Just before sunrise on July 16, 1945, at the secluded Alamogordo Bombing Range in the Central New Mexican desert, a prototype nuclear bomb nicknamed “Gadget” was hoisted to the top of a 100-foot tower and detonated. The blast vaporized the steel tower and produced a mushroom cloud rising to more than 38,000 feet. The heat from the explosion melted the sandy soil around the tower into a mildly radioactive, glassy crust now known as trinitite. The shock wave was powerful enough to break windows 120 miles away. Oppenheimer later recalled that it reminded him of a phrase from the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become Death, destroyer of worlds.”

The implications of the so-called Trinity Test became all too clear on August 6, 1945, when a gun-triggered fission bomb dubbed “Little Boy” fell on Hiroshima, killing an estimated 70,000 to 130,000 people. Three days later, the implosion-triggered “Fat Man” was dropped on Nagasaki, adding another 45,000 human casualties. The United States won the war but at a horrific cost.

Physicists became national heroes, and Oppenheimer became chairman of the AEC. But suspicion over his Communist ties grew stronger, culminating in the infamous 1954 security hearings to determine whether he was guilty of treason. This was at the onset of the McCarthy era, with its paranoid emphasis on rooting out “subversives.” As chair of the Senate Investigations Subcommittee, Senator Joseph McCarthy unveiled a new policy under which a government employee not only had to be judged “loyal,” but his or her background had to be “clearly consistent with the interests of national security.”

Oppenheimer had several Communist acquaintances dating back to the 1930s—including his mistress, Jean Tatlock, who committed suicide in January 1944—and had even implicated some of his friends as Soviet agents under pressure during a 1942 inquiry. He later admitted that testimony had been a “tissue of lies.” In fact, Oppenheimer was the only person who had been approached by Haakon Chevalier, a Berkeley professor of French literature, at a private dinner at Oppenheimer’s house. At the time Groves interceded on Oppenheimer’s behalf, deeming him “absolutely essential” to the success of the Manhattan Project. The “Chevalier incident” was cited as evidence against him during the 1954 hearings. Oppenheimer’s outspoken opposition to the hydrogen bomb did little to allay suspicion.

During the hearings, Edward Teller—who had clashed with Oppenheimer over developing the hydrogen bomb—testified against his former colleagu, telling the commission, “I would prefer to see the vital interests of this country in hands that I understand better and therefore trust more.” Many scientists felt this was an unforgivable betrayal of a colleague, and ostracized Teller from their ranks. Oppenheimer himself denied being a member of the Communist Party, but admitted to being a “fellow traveler,” in that he agreed with many of its goals.

The AEC found Oppenheimer innocent of treason, but ruled he was “not reliable or trustworthy” and thus should not have access to military secrets. His security clearance was revoked on the grounds of “fundamental defects of character,” and for Communist associations “far beyond the tolerable limits of prudence and self-restraint” expected of those holding high government positions.

Getty Images

The lone dissenting opinion among the members of the AEC came from Commissioner Henry DeWolf Smyth, who found no evidence that Oppenheimer had ever divulged secret information during nearly 11 years of constant surveillance. Smyth, a physics professor at Princeton University, believed the charges against Oppenheimer were supplemented by “enthusiastic amateur help from powerful personal enemies,” and concluded that, far from being a Communist subversive, the physicist was “an able, imaginative human being with normal human weaknesses and failings.” Einstein and 25 Princeton colleagues joined the Federation of American Scientists in protesting the AEC’s decision.

But the damage had been done. Oppenheimer didn’t lose his post-war position at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, but he was in academic exile from his former prominent career in government and science policy. By many accounts, he was a broken man after the hearings, although he had enough fire left to strenuously object to a 1964 play dramatizing the hearings: “The whole damn thing was a farce and these people are trying to make a tragedy out of it.”

A partial rehabilitation of his reputation began in 1963, when Oppenheimer was chosen as recipient of the Enrico Fermi Award—nominated by none other than Teller. (President John F. Kennedy was supposed to present the award but was assassinated later that year; his successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, presented it instead.) Oppenheimer died of cancer in 1967.

Science historians have long argued that the revocation of Oppenheimer’s security clearance should be overturned. In 2014, several transcripts from the 1954 hearings were declassified, revealing no damning evidence against the late physicist. Rather, the testimony tended to exonerate him. “It’s hard to see why it was classified,” Cornell University historian Richard Polenberg told the New York Times at the time. “It’s hard to see a principle here—except that some of the testimony was sympathetic to Oppenheimer, some of it very sympathetic.”

Getty Images

So Granholm’s statement is a welcome development, albeit 68 years late. Here is the full text of that statement:

Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer occupies a central role in our history for leading the nation’s atomic efforts during World War II and planting the seeds for the Department of Energy’s national laboratories—the crown jewels of the American research and innovation ecosystem.

In 1954, the Atomic Energy Commission revoked Dr. Oppenheimer’s security clearance through a flawed process that violated the Commission’s own regulations. As time has passed, more evidence has come to light of the bias and unfairness of the process that Dr. Oppenheimer was subjected to while the evidence of his loyalty and love of country have only been further affirmed. The Atomic Energy Commission even selected Dr. Oppenheimer in 1963 for its prestigious Enrico Fermi Award citing his “scientific and administrative leadership not only in the development of the atomic bomb, but also in establishing the groundwork for the many peaceful applications of atomic energy.”

The Department of Energy has previously recognized J. Robert Oppenheimer in other ways including the creation of the Oppenheimer Science and Energy Leadership Program in 2017 to support early and mid-career scientists and engineers to “carry on [Dr. Oppenheimer’s] legacy of science serving society.”

As a successor agency to the Atomic Energy Commission, the Department of Energy has been entrusted with the responsibility to correct the historical record and honor Dr. Oppenheimer’s profound contributions to our national defense and the scientific enterprise at large. Today, I am pleased to announce the Department of Energy has vacated the Atomic Energy Commission’s 1954 decision In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer.

“I’m overwhelmed with emotion,” Kai Bird, co-author with Martin J. Sherwin of the 2005 Pulitzer Prize-winning Oppenheimer biography.American Prometheus, told the New York Times. “History matters and what was done to Oppenheimer in 1954 was a travesty, a black mark on the honor of the nation. Students of American history will now be able to read the last chapter and see that what was done to Oppenheimer in that kangaroo court proceeding was not the last word.”

The day after Granholm’s announcement, the first official trailer dropped for Christopher Nolan’s forthcoming film, Oppenheimer, based on American Prometheus. Cillian Murphy stars as Oppenheimer, flanked by an all-star cast that includes Emily Blunt, Matt Damon, Robert Downey, Jr., Florence Pugh, Kenneth Branagh, Josh Hartnett, David Krumholtz, and Matthew Modine. The trailer naturally focuses on the drama surrounding the birth of the atomic bomb, but if the film follows the arc of the book, Oppenheimer’s fall from grace will also feature prominently.

Official trailer for Oppenheimer, coming to theaters on July 21, 2023.