Real-time video capturing the stretching of an 8×6-inch structural color pattern that features a flower bouquet in homage to 19th-century physicist Gabriel Lippmann’s work.

The bright iridescent colors in butterfly wings or beetle shells don’t come from any pigment molecules but from how the wings are structured—a naturally occurring example of what physicists call photonic crystals. Scientists can make their own structural colored materials in the lab, but it can be challenging to scale up the process for commercial applications without sacrificing optical precision.

Now MIT scientists have adapted a 19th-century holographic photography technique to develop chameleon-like films that change color when stretched. The method can be easily scaled while preserving nanoscale optical precision. They described their work in a new paper published in the journal Nature Materials.

In nature, scales of chitin (a polysaccharide common to insects) are arranged like roof tiles. Essentially, they form a diffraction grating, except photonic crystals only produce specific colors, or wavelengths, of light, while a diffraction grating will produce the entire spectrum, much like a prism. Also known as photonic band gap materials, photonic crystals are “tunable,” which means they are precisely ordered to block certain wavelengths of light while letting others through. Alter the structure by changing the size of the tiles, and the crystals become sensitive to a different wavelength.

Creating structural colors like those found in nature is an active area of materials research. Optical sensing and visual communication applications, for instance, would benefit from structurally colored materials that change hue in response to mechanical stimuli. There are several techniques for making such materials, but none of those methods can both control the structure at the small scales required and scale up beyond laboratory settings.

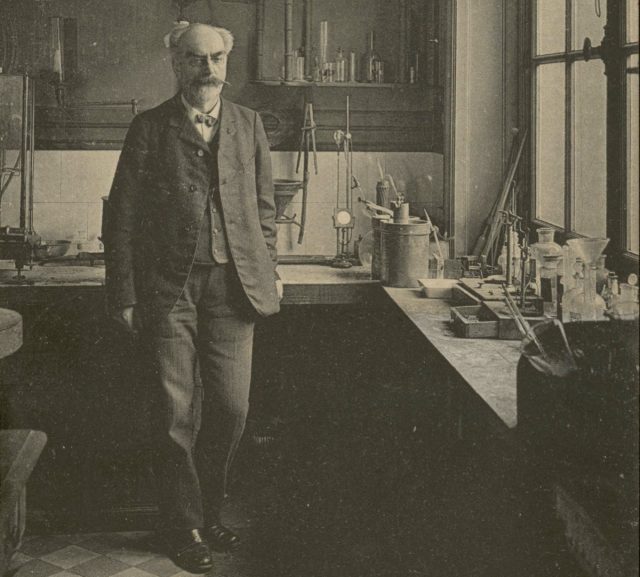

Then co-author Benjamin Miller, a graduate student at MIT, discovered an exhibit on holography at the MIT Museum and realized that creating a hologram was similar in some respects to how nature produces structural color. He delved into the history of holography and learned about a late 19th-century color photography technique invented by physicist Gabriel Lippmann.

As we’ve reported previously, Lippmann became interested in developing a means of fixing the colors of the solar spectrum onto a photographic plate in 1886, “whereby the image remains fixed and can remain in daylight without deterioration.” He achieved that goal in 1891, producing color images of a stained-glass window, a bowl of oranges, and a colorful parrot, as well as landscapes and portraits—including a self-portrait.

Lippmann’s color photography process involved projecting the optical image as usual onto a photographic plate. The projection was done through a glass plate coated with a transparent emulsion of very fine silver halide grains on the other side. There was also a liquid mercury mirror in contact with the emulsion, so the projected light traveled through the emulsion, hit the mirror, and was reflected back into the emulsion.

Real-time stretching of the structural color material integrated as a colorimetric pressure sensor in a bandage. The video was shot outdoors to demonstrate the robust colour response under natural lighting.