Henry Sharpe

New research indicates that the tail clubs on huge armored dinosaurs known as ankylosaurs may have evolved to whack each other rather than deter hungry predators. This is a complete shift from what was previously believed.

Prior to the paper published today in Biology Letters, most scientists looked upon the dinosaur’s tail club, a substantial bony protrusion comprised of two oval-shaped knobs, primarily as a defense against predation. The team behind the new paper argues that this is not necessarily the case. To make their case, they focus on years of ankylosaur research, analysis of the fossil record, and data from an exceptionally well-preserved specimen named Zuul crurivastator.

Zuul’s name, in fact, embraces that previous idea. While “Zuul” references the creature in the original Ghostbusters, the two Latin words that make up its species name are crus (shin or shank) and vastator (destroyer). Hence, the destroyer of shins: a direct reference to where the dinosaur’s club may have struck approaching tyrannosaurs or other theropods.

But that name was given when only its skull and tail had been excavated from the rock where the fossil was encased. After years of skilled work by the fossil preparators at the Royal Ontario Museum, Zuul’s entire back and flanks are exposed, offering important clues as to what its tail club might target.

Target identification

Lead author Dr. Victoria Arbour is currently the Curator of Paleontology at the Royal British Columbia Museum, but she’s a former NSERC postdoctoral fellow at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. That’s been Zuul’s home since 2016, two years after its initial discovery in Montana. She’s spent years studying ankylosaurs, a type of dinosaur that appear in the fossil record from the Jurassic through the end of the Cretaceous. Some species of ankylosaurs have tail clubs, while others, known as nodosaurs, do not. That difference raises some questions about what these structures were used for.

“I think a natural follow-up question from, ‘Could they use their tail clubs as a weapon?’ is ‘Who are they using that weapon against?’” Arbour explained. “And so that’s where I really started thinking about this.

Back in 2009, she authored a paper that suggested ankylosaurs might use their tail clubs for intraspecific combat—fights with other ankylosaurs. That work focused on the potential impact of tail clubs when used as a weapon, especially as the clubs come in various shapes and sizes, and in some species, weren’t even present until the animal matured. Measuring available fossil tail clubs and estimating the force of the blows they could produce, she found that smaller clubs (approximately 200 millimeters or half a foot) were too small to be used as a defense against predators.

Zuul crurivastator, the shin-basher.

Royal Ontario Museum

She recommended further research, noting that if ankylosaurs were using them for intraspecific combat, one might expect to see injuries along adult flanks, as an ankylosaur tail can only swing so far.

It’s one thing to have an idea about an extinct animal, but it’s another to have evidence. Ankylosaur fossils are rare in general; dinosaurs with preservation of the tissues that would have been damaged in these fights are much rarer. So it’s astounding that Arbour could test her ideas thanks to an animal with its entire back—most of its skin and all—intact.

“I put out this idea that we would expect to see damage on the flanks, just based on how they might line up against each other,” Arbour told Ars. “And then a decade and a bit later, we get this amazing skeleton of Zuul with damage right where we thought we might see it. And that was pretty exciting!”

Damage assessment

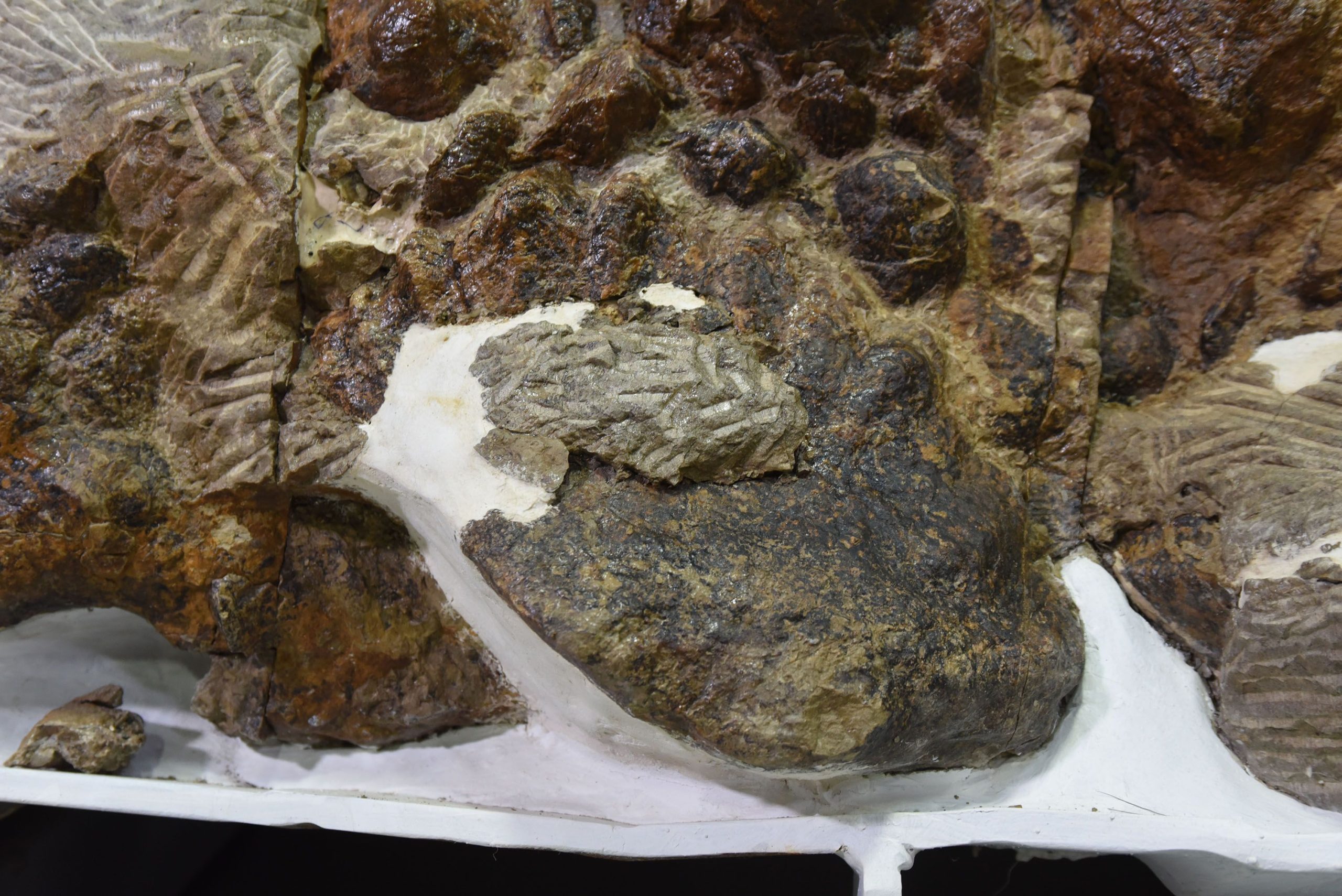

Zuul’s back and flanks are covered in various spikes and bony structures called osteoderms. Just as Arbour predicted, there is evidence of broken and injured osteoderms on both sides of the flanks, some of which appear to have healed.

“We also did some sort of basic statistics to show that the injuries are not randomly distributed on the body,” she continued. “They really are just restricted to the sides in the areas around the hips. That can’t be explained just by random chance. It seems more likely that it’s [the result of] repeated behavior.”

A damaged but partly healed spike on the side of Zuul.

Royal Ontario Museum

There are only a handful of well-preserved ankylosaurs, including at least one of a nodosaur named Borealopelta at the Royal Tyrrell Museum. The authors note that there aren’t any comparable injuries on known nodosaurs, a germane point. As mentioned previously, nodosaurs don’t have tail clubs and thus wouldn’t have been able to use them against each other.

Equally important, the damage isn’t accompanied by evidence of predation. No bite marks, puncture wounds, or tooth scratches are found anywhere on Zuul’s body.