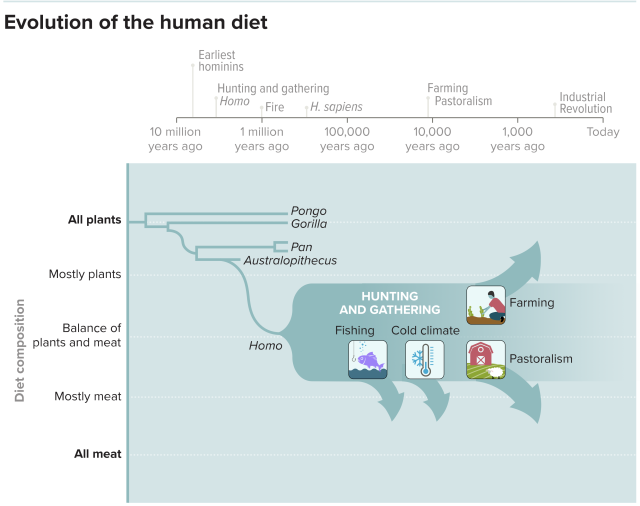

What did people eat for dinner tens of thousands of years ago? Many advocates of the so-called Paleo diet will tell you that our ancestors’ plates were heavy on meat and low on carbohydrates—and that, as a result, we have evolved to thrive on this type of nutritional regimen.

The diet is named after the Paleolithic era, a period dating from about 2.5 million to 10,000 years ago when early humans were hunting and gathering, rather than farming. Herman Pontzer, an evolutionary anthropologist at Duke University and author of Burn, a book about the science of metabolism, says it’s a myth that everyone of this time subsisted on meat-heavy diets. Studies show that rather than a single diet, prehistoric people’s eating habits were remarkably variable and were influenced by a number of factors, such as climate, location and season.

In the 2021 Annual Review of Nutrition, Pontzer and his colleague Brian Wood, of the University of California, Los Angeles, describe what we can learn about the eating habits of our ancestors by studying modern hunter-gatherer populations like the Hadza in northern Tanzania and the Aché in Paraguay. In an interview with Knowable Magazine, Pontzer explains what makes the Hadza’s surprisingly seasonal, diverse diets so different from popular notions of ancient meals.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What do today’s Paleo diets look like? How well do they capture our ancestors’ eating habits?

People have developed many different versions, but the original Paleo diet is quite meat-heavy. I would say the same is true of the predominant Paleo diets today—most are very meat-heavy and low-carb, downplaying things like starchy vegetables and fruits that would only have been seasonally available before agriculture. There’s also an even more extreme camp within that, which says that humans used to be almost entirely meat-eating carnivores.

But our ancestors’ diets were really variable. We evolved as hunter-gatherers, so you’re hunting and gathering whatever foods are around in your local environment. Humans are strategic about what foods they go after, but they can target only the foods that are there. So there was a lot of variation in what hunter-gathers ate depending on location and time of year.

The other thing is that, partly due to that variability, but also partly due just to people’s preferences, there’s a lot of carbohydrate in most hunter-gatherer diets. Honey was probably important throughout history and prehistory. A lot of these small-scale societies are also eating root vegetables like tubers, and those are very starch- and carb-heavy. So the idea that ancient diets would be low-carbohydrate just doesn’t fit with any of the available evidence.

So how did “Paleo” come to represent meat-heavy and low-carb eating?

I think there are a couple of reasons for that. You have a kind of romanticizing of what hunting and gathering was like. There is a sort of macho caveman view of the past that permeates a lot of what I read when I look at Paleo diet websites.

There are also inherent biases in a lot of the available archaeological and ethnographic data. In the early 1900s, and even before, a lot of the ethnographic reports were written by men who focused on men’s work. We know that traditionally that’s going to focus more on hunting than on gathering because of the way a lot of these small-scale societies divide their work: Men hunt and women gather.

On top of that, the available ethnographic data is heavily skewed toward very northern cultures, such as Arctic cultures—since the warm-weather cultures were the first ones to get pushed out by farmers—and they do tend to eat more meat. But our ancestors’ diets were variable. Populations that lived near the ocean and moving rivers ate a lot of fish and seafood. Populations that lived in forested areas or in places rich in vegetation focused on eating plants.

There is also a bias toward hunting in the archaeological record. Stone tools and cut-marked bones—evidence of hunting—preserve very well. Wooden sticks and plant remains don’t.