Earlier this year, news broke of the first experimental xenotransplantation: A human patient with heart disease received a heart from a pig that had been genetically engineered to avoid rejection. While initially successful, the experiment ended two months later when the transplant failed, leading to the death of the patient. At the time, the team didn’t disclose any details regarding what went wrong. But this week saw the publication of a research paper that goes through everything that happened to prepare for the transplant and the weeks following.

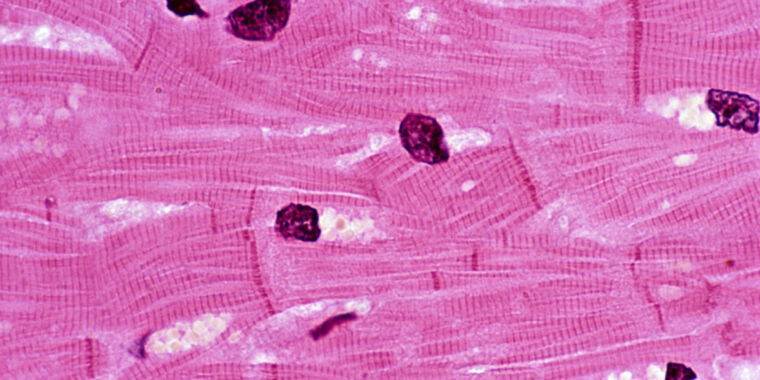

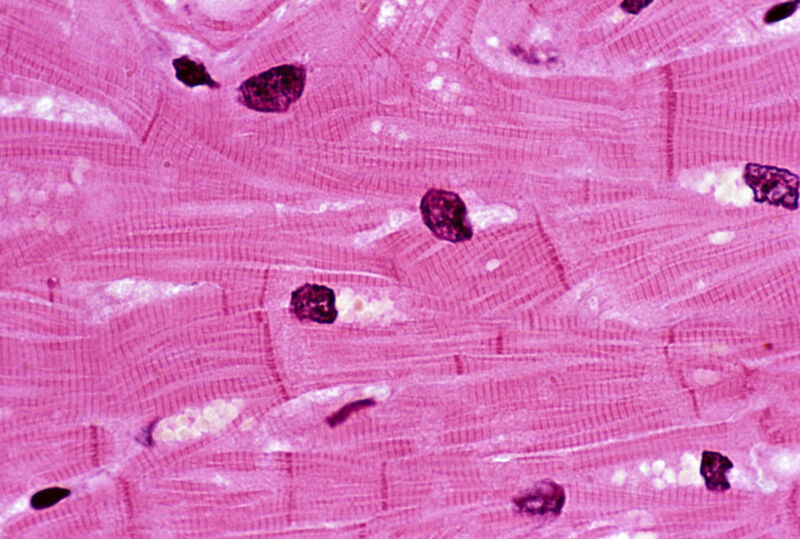

Critically, this includes the eventual failure of the transplant, which was triggered by the death of many of the muscle cells in the transplanted heart. But the reason for that death isn’t clear, and the typical signs of rejection by the immune system weren’t present. So, we’re going to have to wait a while to understand what went wrong.

A solid start

Overall, the paper paints a picture of organ recipient David Bennett as a patient who was on the verge of death when the transplant took place. He was an obvious candidate for a heart transplant and was only kept alive through the use of a device that helped oxygenate his blood outside his body. But the patient had what the researchers refer to as “poor adherence to treatment,” which led four different transplant programs to deny him a human heart transplant. At that point, he and his family agreed to participate in the experimental xenotransplant program.

The pig that served as the heart donor came from a population that has been extensively genetically engineered to limit the possibility of rejection by the human immune system. The line was also free of a specific virus that inserts itself into the pig genome (porcine endogenous retrovirus C, or PERV-C) and was raised in conditions that should limit pathogen exposure. The animal was also screened for viruses prior to the transplant, and the patient was screened for pig pathogens afterward.

After the transplant, the patient’s new heart performed well, displaying a normal rhythm between 70 and 90 beats per minute. Most significantly, over half the blood that filled the left ventricle of the transplanted heart was sent out into the circulatory system with each contraction; that was up from only 10 percent in the diseased heart it had replaced.

At about two weeks after the transplant, Bennett started experiencing abdominal pain and weight loss that ultimately resulted in him losing more than 20 kg (40 lbs). He was put on a feeding tube, and an exploratory laparoscopy showed potential signs of an infection that was resolving, but no action was deemed needed. A short while later, screening turned up a possible infection with the pig version of cytomegalovirus; the human version of this virus causes issues like pneumonia and mononucleosis. This was handled with antiviral treatments.

While the weight loss was an obvious concern, at five weeks after the transplant, there were no indications of rejection, and the heart was still functioning.