Hebrides Overture’s disappearing notes highlight the plight of humpback whales.

Felix Mendelssohn’s The Hebrides was inspired by the composer’s 1829 trip to the British Isles. His overture has now inspired collaboration between a Cambridge economist and a composer, using sound to call attention to the loss of biodiversity on Earth. Hebrides Redacted successively removes notes from the 10- to 11-minute overture in proportion to the decline in humpback whale populations over many decades. A short film about the project (embedded above) was released today as part of the Cambridge Zero Climate Change Festival.

“Over the past century we have seen nearly a million species pushed to the brink of extinction—nature is going quiet,” said Matthew Agarwala, an economist at the University of Cambridge. “Researchers—including me—have been sounding the alarm about the consequences of biodiversity loss for a long time, but the message isn’t landing. Music is visceral and emotional, and grabs people’s attention in ways that scientific papers just can’t.”

Mendelssohn visited England and Scotland at the invitation of the Philharmonic Society. It was during his tour of Fingal’s Cave on the Scottish island of Staffa that inspiration struck, and he quickly wrote down the opening theme that came to him. The opening notes feature violas, cellos, and bassoons to evoke the cave’s beauty, while a secondary theme is meant to convey the rolling waves of the sea.

He finished the piece in June 1832 and conducted the first performance in January 1833 in Berlin. It’s widely considered one of his greatest compositions, sometimes described as a tone poem. No less a luminary than Johannes Brahms once declared, “I would gladly give all I have written to have composed something like the Hebrides overture.”

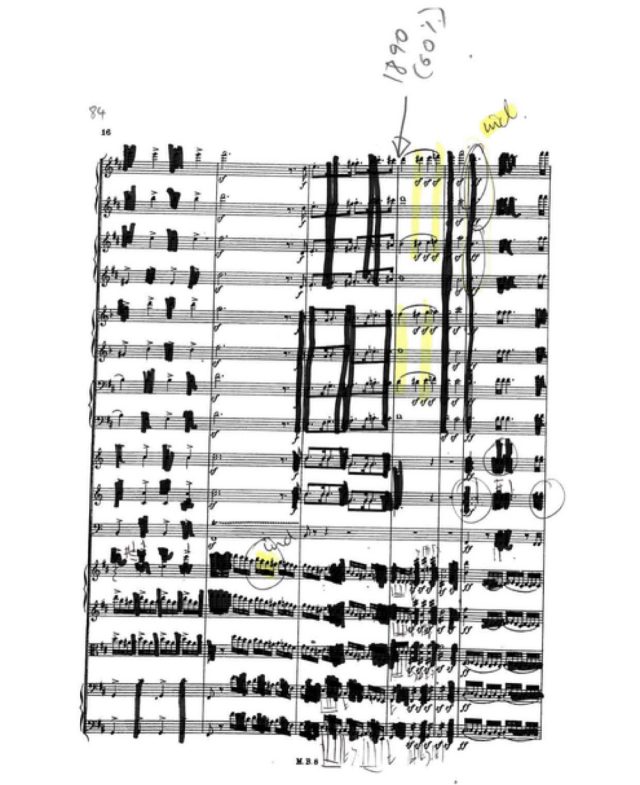

Per Agarwala, there are about 30,000 notes in Mendelssohn’s original score, which roughly corresponds to the number of humpback whales that populated the oceans in 1829. But a thriving whaling industry reduced their numbers to the brink of extinction. By the 1960s, there were only around 5,000 humpback whales left, and the International Whaling Commission (IWC) banned commercial humpback whaling as a protective measure.

Ewan Campbell

The species has since rebounded, with a 2018 worldwide population of around 135,000 whales, 13,000 of which call the North Atlantic home. But they still face threats like getting entangled in fishing gear, colliding with vessels, and excessive ocean noise, as well as the destruction of their coastal habitats and adverse impacts of climate change.

That’s why Agarwala and composer Ewan Campbell chose to build Hebrides Redacted around the plight of those creatures, figuring it was highly likely that during his trip, Mendelssohn would have seen a humpback whale or two—or hundreds. Campbell divided the score into sections to represent decades, and gradually removed notes according to how the whale populations declined over those decades. Yet the piece ends optimistically, allowing for an 8 percent rise every decade in whale populations in the future.

“At its nadir, the score is thin and fragmented, with isolated notes reaching for a tune that is only partially present,” said Campbell. “But even in the face of devastating destruction, nature is resilient and always beautiful, and so even when two-thirds of the music is absent there’s still a delicate beauty, though a pale imitation of its once dramatic glory. ‘Redaction’ is a word normally associated with censorship, and silencing history. I find it really apt for this piece of music. We’re showing how human activities have silenced nature.”

Hebrides Redacted received a standing ovation when it was performed by a 38-piece orchestra at the August Wilderness Festival in Oxfordshire, England, with Campbell conducting and Agarwala narrating.