Public domain

Former FBI special agent Vincent Pankoke was looking forward to a relaxing retirement hanging out at the beach when he left the agency. Instead, he was drawn into solving a famous cold case: the question of who betrayed Anne Frank and her family to the Nazis, leading to their arrest and deportation to a concentration camp. Only the father, Otto Frank, survived. To find his own answer to that question, Pankoke assembled his own crack team of dogged investigators. They spent five years poring over every bit of pertinent material, setting up an extensive online database, and developing an AI program to help them sift through it all and find new connections.

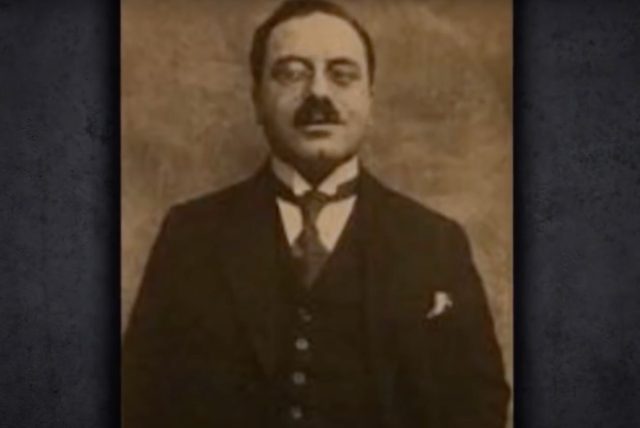

While admitting that the case is circumstantial and some reasonable doubt remains, Pankoke et al. believe the most likely culprit is a man named Arnold van den Bergh, a local Jewish leader who may have handed over lists of addresses where fellow Jews were hiding to the Nazis in order to protect his own family. The Pankoke team’s story was featured in a segment on 60 Minutes earlier this week (see video at end of post), and is covered in detail in a new book by Rosemary Sullivan, The Betrayal of Anne Frank: A Cold Case Investigation.

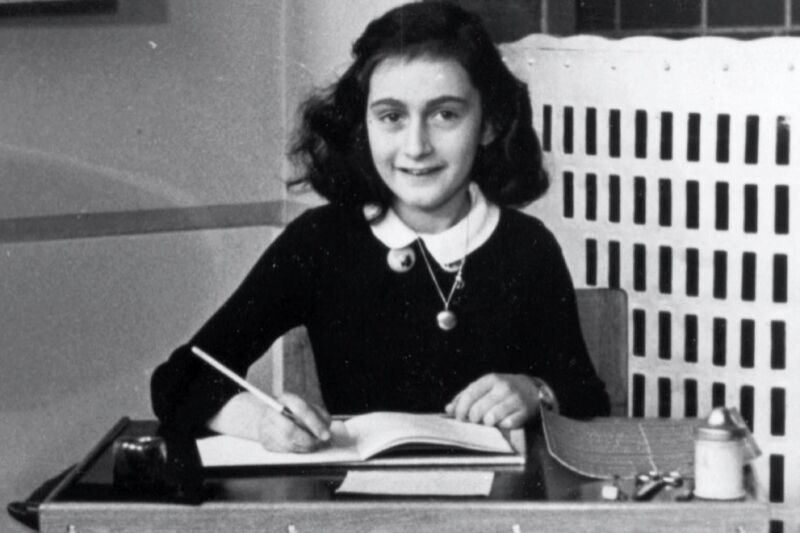

Millions of people have read The Diary of Anne Frank since it was first published posthumously in 1947. It’s been translated into 70 languages and inspired a theatrical play and subsequent Oscar-winning 1959 film, featuring Millie Perkins in the title role. Anne Frank was born in Frankfurt, Germany, but the family fled the country and settled in Amsterdam after Adolf Hitler came to power. They didn’t flee quite far enough: the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands began in May1940 and eventually forced the Franks (and many other Jews) into hiding.

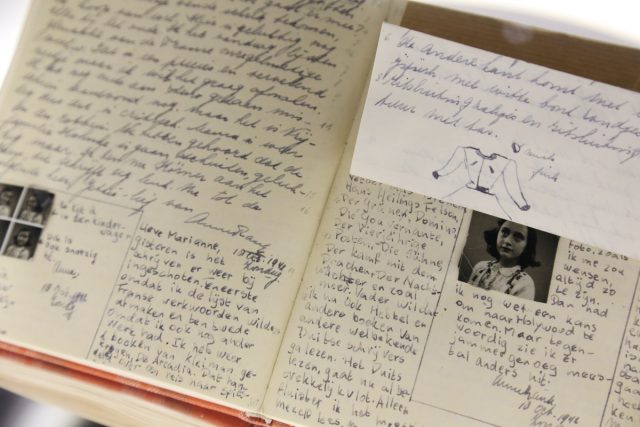

Anne received the famous diary on June 12, 1942 for her 13th birthday, around the time the Gestapo began deporting Jews in Amsterdam. On July 6, the Frank family began their lives in the Secret Annex attached to the office building at Prinsengracht 263, where Otto Frank had worked. It was only accessible via a door on the landing, kept hidden by a bookcase. Victor Kugler, Johannes Kleiman, Miep Gies, and Bep Voskuijl were the only employees who knew where the Franks (and later, the Van Pels family) were hiding. The four supplied the families with food and other necessities, knowing full well that they could be condemned to death by the Nazis for aiding Jews.

Anne chronicled their lives in the Annex in her diary for the next two years, making her final entry on August 1, 1944. Just three days later, German police led by SS officers stormed the Annex, arresting the Franks and the Van Pels family and transferring them to the Westerbork transit camp after interrogation. Kugler and Kleiman were also arrested and held at a penal camp for “enemies of the regime.”

Gies and Voskuijl were questioned, but not detained, and found the pages of Anne’s diary strewn around the floor when they returned to the Annex, preserving it for posterity. As the whole world now knows, 15-year-old Anne Frank died (likely of typhoid fever) at Bergen-Belsen between February and April, 1945, the day after her older sister Margot. Their mother, Edith, had died of starvation the year before.

Katie Falkenberg/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images

There were two separate official investigations into who may have betrayed the family: one in 1947-1948, and the second (conducted by the Dutch police) in 1963-1964. In both cases, the findings were inconclusive. Since then, there have been several independent investigations identifying different possible suspects.

For instance, Melissa Muller’s 1998 biography of Anne Frank concluded that a woman named Lena Hartog, wife of the company’s assistant warehouse manager, betrayed the family. In 2003, Carol Ann Lee came to a different conclusion in her biography of Otto Frank: the culprit was a man named Anton “Tonny” Ahlers, a member of the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands. Stockroom manager Willem van Maaren was another suspect, and since several possible culprits knew each other, there is also the possibility that more than one person betrayed the Frank family.

A 2015 biography of Bep Voskuijl (co-authored by her son Joop) suggested that one of Bep’s sisters, Nelly, may have snitched on the Franks. Nelly fell in love with a young Austrian Nazi, had worked for a year on a German air base, and her political leanings had sufficiently estranged her from the family that she left their house. This theory holds that Nelly—who returned to Amsterdam in 1943 when her romance soured—may have been the anonymous female caller who (allegedly) tipped off the SS about the secret Annex, per the testimony of SS officer Karl Josef Silbauer, who made the arrests.

The Anne Frank House undertook its own investigation and arrived at a surprising new theory in 2017, thanks to the efforts of a historian named Gertjan Brock. It’s possible, Brock suggested, that there was no betrayal, and the SS raid was really part of ongoing attempts to track down purveyors of illegal goods. This theory holds that the officers just happened to stumble upon the Jewish families hiding in the attic.

Getty Images

Brock relied on Anne’s diary entries from March 1944 to confirm that the SS may have received a tip about ration coupon fraud or illegal workers, prompting the raid on Prinsengracht 263. Several diary entries noted the arrest of two men (identified only as “B” and “D,” for Martin Brouwer and Peter Daatzelaar) who trafficked in illegal ration cards. “B and D have been caught so we have no coupons,” Anne wrote on March 14.

This would almost certainly have attracted the attention of the authorities. Also, police reports indicated that the officers who arrested the Annex residents had primarily worked on cases involving cash, securities, and jewelry, rather than focusing on hunting down Jews. Those officers spent over two hours searching the property, suggesting they were looking for something other than the Jewish families.

All of these theories, and more, were considered and carefully studied by Pankoke and his team (standard cold case procedure). They enlisted the services of an Amsterdam-based data company called Xomia, who provided the foundation for a Web-based AI program developed by Microsoft. “[I]t would enable the team to marshal the millions of details surrounding the case and make connections among people and events that had been overlooked before,” Sullivan wrote.

Xomia’s scientists warned the team that because it was such an old case, with so much missing data, it was highly unlikely that even their advanced AI system would be able to completely solve the puzzle. However, the program would be enormously helpful in narrowing down the suspects and predicting the most likely candidate(s).

20th Century-Fox/Getty Images

Of course, first they had to build a database by digitizing the many historical accounts and official records of what had happened. In addition to scanning, the program could convert video and audio recordings to text, translate them into English, and make the database searchable. Many street names in Amsterdam had changed since World War II, so the AI also included a program capable of converting street names from a current map to a WWII era map, complete with geolocation tags for all the relevant addresses.

Among the links that the program revealed were previously unknown connections between policemen who went on the same raids and female informants who had worked together. Team member Pieter van Twisk gave Sullivan an example of just how useful the program could be:

If for instance, an address of interest came up in one of the files I was examining, I could very quickly cross-reference it within the database. Running the address through the AI would provide me with all relevant documents or other sources in the data store in which this address was mentioned. Sources where it was mentioned the most would appear highest. It could also give me a graphic on how this address was connected to other relevant items such as different people who were somehow connected to this address. It could provide a map with all the connections between this address and others and would indicate which connections were the most common. It could also provide a timeline of when and where this address was most relevant.

The investigation also incorporated modern law enforcement techniques such as behavioral science (profiling), crowdsourcing, and forensic testing. Investigative psychologist Bram van der Meer was tasked with analyzing the data collected on all the witnesses, victims, and other persons of interest so he could profile them, noting especially their likely behavioral responses and decision-making in unusual or stressful situations.

YouTube/60 Minutes/CBS

All this helped the team identify about 30 different potential theories for why the SS had raided the Annex, and they closely examined each one—a process that led them down the occasional rabbit hole. Sullivan’s book covers several potential candidates in great detail.

For instance, one of many interviews Pankoke and his team conducted was with an elderly Holocaust survivor whose own family had been hiding in another house on the Prinsengracht, and had been betrayed to the Nazis shortly before the Frank family. The culprit in that instance was a woman named Anna van Dijk, a well-known informant. There was also a policeman who had participated in both raids, yielding helpful information about both operations, especially their similarities.

Van Dijk seemed like a promising candidate for the Frank family’s betrayal, especially given her role in the arrest of a Jewish couple who had been hiding in Utrecht. According to Sullivan’s account, the couple were friendly with the Frank family, traveling to Amsterdam every month to get food. They were arrested on one such trip, and van Dijk posed as a fellow prisoner, convincing them to reveal where other Jewish people might be hiding—ostensibly to “warn” them to relocate in case the couple cracked under interrogation.

YouTube/60 Minutes/CBS

Alas, the official reports Pankoke and his team finally dug up revealed that the couple had been arrested several weeks after the Annex raid, and there was no mention of a female informant’s involvement. Van Dijk and her husband weren’t even in Amsterdam in August 1944, having moved to a small town near Utrecht to infiltrate a resistance network.

By the spring of 2019, the possible theories had been winnowed down to twelve, further reduced to just four possibilities by midsummer—either because the team had concluded the discarded theories were improbable, or there simply wasn’t enough available information to warrant additional investigation. Among the discarded candidates was Nelly Voskuijl, whom Panoke et al. had initially taken seriously as a suspect. But then they found an interview with Otto Frank by a Dutch journalist in the late 1940s. Otto claimed that “they’d been betrayed by Jews and he did not wish to pursue the culprit because he did not wish to punish the family and children of the man who had betrayed them,” Sullivan wrote.

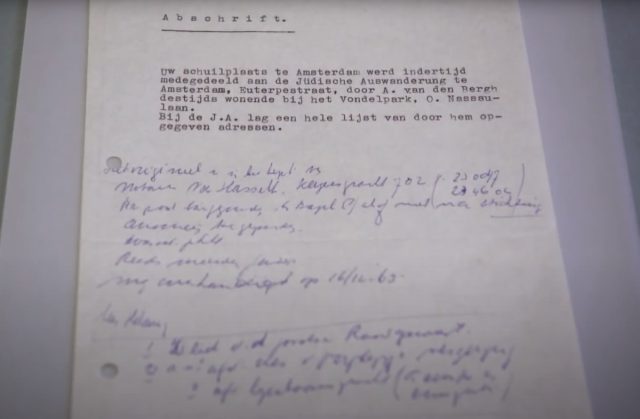

This focused the team’s attention on van den Bergh, especially since his possible culpability was bolstered by a piece of actual physical evidence. Someone had sent Otto an anonymous note. The note informed him that their family hideout had been revealed to the Jewish Council, a body forced to implement Nazi policy in the Jewish areas of Amsterdam. Van den Bergh was a member, and was named in the note. The original note has been lost, but Otto had made a copy of it, indicating he found the tip to be credible. The Council was disbanded in 1943, and its members were sent to concentration camps—all except for van den Bergh, who continued to live in Amsterdam. He died in 1950.

YouTube/60 Minutes/CBS

From Pankoke’s perspective, van den Bergh met all the standard law enforcement criteria. He insists that the Jewish Council almost certainly maintained lists of Jews in hiding, and as a member, van den Bergh would have had access to them. He also had a motive: protecting himself and his family from capture and deportation, by providing the Nazis with useful information. Finally, van den Bergh had opportunity, because he was free to move about, and was in regular contact with highly placed Nazis, so he could have passed on a list of addresses at any time.

This was also the only possibility consistent with Otto’s own cryptic statements over the years, although Pankoke’s reasoning on Otto’s behavior and motivations for keeping van den Bergh’s identity a secret are largely speculative. “Perhaps he just felt that if I bring this up again… it’ll only stoke the fires [of anti-Semitism] further,” Pankoke told 60 Minutes. “But we have to keep in mind that the fact that [van den Bergh] was Jewish just meant that he was placed in an untenable position by the Nazis to do something to save his life.”

The identification of van den Bergh has naturally caused a stir, although there is still skepticism about whether Pankoke et al.’s conclusion is correct. University of Leiden historian Bart van der Boom dismissed the theory as “defamatory nonsense” to the BBC, while Amsterdam University’s Johannes Houwink insisted that if lists of Jews in hiding had existed, they would have surfaced long before now. The Anne Frank House was more circumspect in its reaction, stating that the Pankoke team’s investigation was impressive, and had “generated important new information and a fascinating hypothesis that merits further research.”

A retired FBI special agent and a team of investigators believe they’ve solved one of the world’s most well-known and tragic cold cases.