Dara Orbach

Female dolphins are known to be highly social and engage in all sorts of sexual behavior. In addition to mating with male dolphins, female bottlenose dolphins are, for instance, known to masturbate and also rub each other’s clitoris with snouts, flippers, and flukes, suggesting the acts are pleasurable for them. According to a recent paper published in the journal Current Biology, there is now anatomical evidence that the dolphin clitoris is fully functional, remarkably similar in many ways to the clitoris in human females.

It’s not just dolphins that engage in what Canadian biologist and linguist Bruce Bagemihl has dubbed “biological exuberance.” Same-sex pairings have been recorded in some 450 different species, including flamingoes, bison, warthogs, beetles, and guppies. For instance, female koalas sometimes mount other females, while male Amazon river dolphins have been known to penetrate each other’s blowholes. The observation of female-female pairs among Laysan albatrosses made national headlines, prompting comedian Stephen Colbert to warn satirically that “albatresbians” were threatening American family values with their “Sappho-avian agenda.” Female hedgehogs may hump one another or perform cunnilingus, while 60 percent of all sexual activity among bonobos takes place between two or more females.

Despite this abundance of behavioral evidence, there have been very few academic studies of the clitoris and female sexual pleasure in nature, according to Patricia Brennan, a marine biologist at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts and a co-author of the new study. “This has left us with an incomplete picture of the true nature of sexual behaviors,” she said. “Studying and understanding sexual behaviors in nature is a fundamental part of understanding the animal experience and may even have important medical applications in the future.” It can also yield insights into the evolution of sexual behaviors.

A number of factors contribute to that neglect in the academic literature, said Brennan. “In general, we haven’t studied sexuality, period, as much as we should, because evolutionarily speaking, it’s an absolutely critical process,” she told Ars. “I think it makes some people uncomfortable.” As for why male sexuality has been studied more frequently than female sexuality (in both humans and animals), that’s partly due to inherent biases—until quite recently, the vast majority of scientists were men. Another reason: females are just harder to study in that regard.

“A male penis is just sticking out there,” Brennan said. “Female genitalia are inside, so it’s trickier, and you have to be more creative about coming up with methods to study females.”

That’s the focus of Brennan’s laboratory, specifically studying the evolution of the vagina in dolphins and other animals. Brennan started out working with dolphins as an undergraduate but switched to studying birds (especially ducks) while she worked on her Ph.D. Male ducks are famous for their spectacularly long corkscrew penises, “but nobody had thought to look at the vagina of a duck to see how it would interact with those weird penises,” she said.

P.L.R. Brennan et al., 2022

Brennan did think to look. She found that female ducks have corresponding corkscrew vaginas that spiral in the opposite direction of the male’s penis. “Female ducks are subjected to forced copulations by unwanted males and usually they cannot escape,” Brennan told LiveScience in 2009. “The genital morphology allows them to regain control of reproduction by making it difficult for these unwanted males to achieve fertilization.”

Since then, she’s studied the vaginas of sharks, alpacas, turtles, crocodiles, and snakes, before turning her attention back to dolphins. “Every time we looked at the vaginas, it was like this giant clitoris staring us in the face,” said Brennan. “Just from knowing the behavior of female dolphins, we had a pretty good idea that they were probably enjoying sex. They’re having heterosexual sex, homosexual sex, and they’re masturbating. That suggests this feels good to them.”

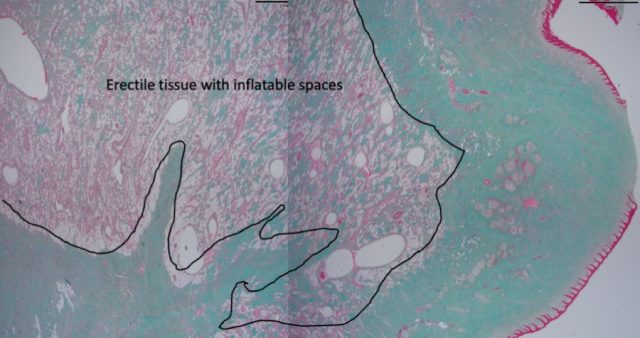

So Brennan decided to take a closer look at excised dolphin clitorises with micro-CT scanning. If the morphology of the dolphin clitoris had shared features with a human clitoris, that would suggest functionality that may provide pleasure during these sexual encounters. The 11 dolphin clitorises used in the study came from animals that had died naturally, such as in strandings.