An ecological model has been applied to estimate the number of lost medieval manuscripts in Europe.

Those who study human culture must grapple with what amounts to an incomplete data set, since researchers are limited to poring over the books, manuscripts, paintings, sculptures, and other artifacts that have survived to learn about a given period. We call this predicament “survivorship bias,” and it can lead to underestimations of just how diverse a society might have been in terms of the cultural materials produced. Teasing out how much of a cultural domain may have been lost is a considerable challenge.

The field of ecology might be able to help. According to a new paper published in the journal Science, an international team of researchers has adapted an ecological “unseen species” model to estimate how many medieval European stories in the chivalric romance or heroic tradition survived and how much has been lost. The authors also presented their findings last week at a virtual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAA).

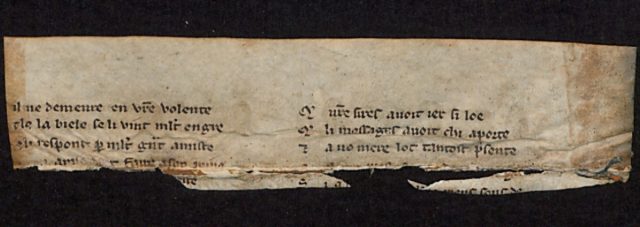

The team looked at medieval works in Dutch, English, French, German, Icelandic, and Irish and concluded that only about 9 percent of medieval manuscripts survived. However, losses were significantly lower in Icelandic and Irish literature, suggesting that island ecosystems might help preserve culture. In fact, the team’s results were very similar to the estimates made by scholars using other data, such as references to lost works that appear in surviving manuscripts.

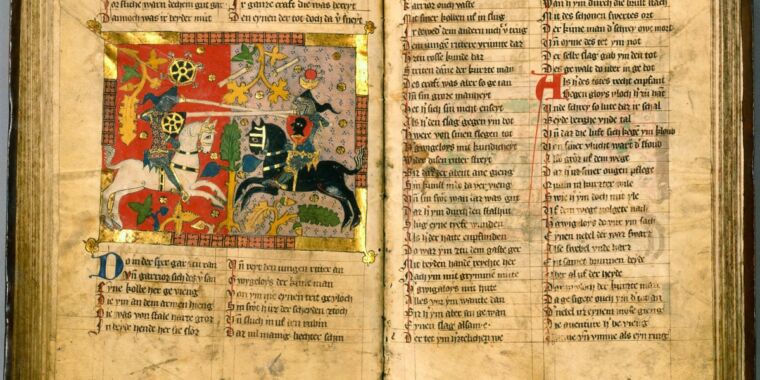

CC-BY University Library Leiden

“A lot of literature went missing, and we don’t know what it is, but using this method we can get some idea, at least, about how much of the jigsaw puzzle is missing,” said co-author Matthew Driscoll of the University of Copenhagen. For instance, Arthurian legend has survived in a very wide range of story cycles, and scholars aren’t likely to have missed a similar highly popular and influential literary tradition. However, “I’m 100 percent certain that there are romances dealing with the Knights of the Round Table that have not survived,” said Driscoll. “There must be. This is exactly where you think, ‘Damn, we could have made a great film about that if we’d had it.'”

The field of ecology uses bias correction in statistical models that can account for so-called unseen species in a given ecosystem to determine the richness of species diversity. The model used in this study is known as the Chao1 method, developed by Anne Chao of National Tsing Hua University, another co-author on the paper.

The idea to adapt Chao’s model came from co-author Folgert Karsdorp of KNAW Meertens Institute, whose research focuses on cultural evolution and looking for methods in biological evolution that might be applicable to the cultural domain. “I was looking for ways of dealing with this selection bias of estimating the cultural population,” said Karsdorp, and when he came upon the Chao1 model, “We figured we might as well try it on this really hard question of lost medieval literature.”

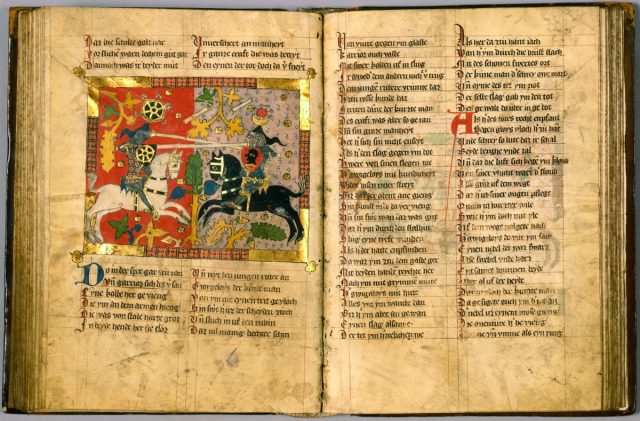

CC-BY Royal Irish Academy (Dublin)

The Chao1 model is meant to give users an accurate estimate of how many species inhabit an area, said co-author Mike Kestemont of the University of Antwerp. First, scientists collect “abundance data,” counting all the animal species they can observe. The issue is that certain hard-to-observe species will be missed in that count. (Snow leopards, for instance, are notoriously difficult to spot.)

The Chao1 formula will look at those species that don’t appear often in the abundance data. If you only spotted a species once, for example, it would be designated “F1.” If you’ve spotted a species twice, it would be F2. Those numbers can then be used to calculate F0—the number of species that have been observed exactly zero times in an area. “Then you have a lower bound on the estimates of the number of species you didn’t observe,” said Kestemont.

But can an ecological model really be applied so readily to such a markedly different scholarly domain? “Intuitively, it’s a weird thing to say that a literary work behaves like a species,” Kestemont acknowledged. “In fact, this method isn’t even specific to ecology.” Chao1 is so general that it’s been used in lots of other fields, with “species” standing in for classes of stone tools (archaeology); types of die for ancient coins (numismatics); different causes for a given disease (epidemiology); genes or alleles (genetics); and distinct vocabulary words (linguistics), to name a few.

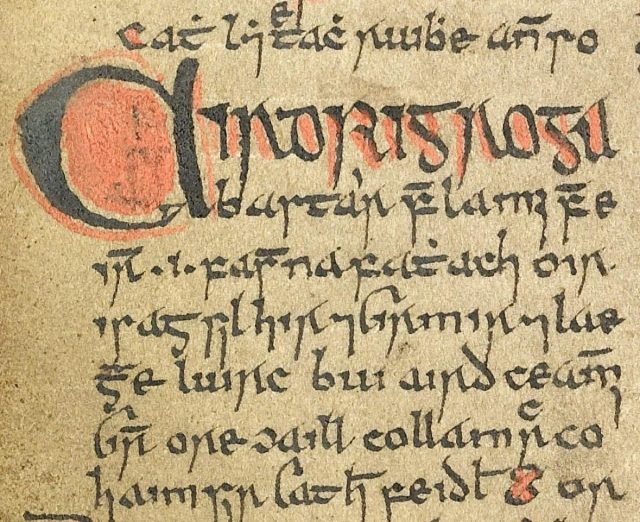

CC-BY Huis Bergh (’s-Heerenberg)

“It’s even been used to estimate the number of stars in a galaxy or the number of bugs in a piece of software that haven’t been discovered yet,” said Kestemont. “The real question is ‘in which conditions wouldn’t we be able to apply it?'” As long as you can distinguish something akin to “species,” the model works very well.

In adapting the model, Kestemont and his co-authors treated literary works as species and manuscript copies as sightings of a species. They counted works that only appeared sparsely in the historical record and then used those counts to calculate F0—in this case, the number of works that once existed but scholars have never observed. A work was considered “lost” when none of the documents that once preserved it still survived.

This approach allowed the researchers to estimate the size of the original population of works and manuscripts as well as the losses sustained across the Dutch, French, Icelandic, Irish, English, and German vernaculars. They found that there would have been 40,614 specimens (manuscripts) across all six vernaculars, of which 3,649 still survive—a 9 percent survival rate. As for literary species (works), 38 percent have survived.

The method also produced “evenness” profiles for each of the six vernaculars included in the study, an aspect the researchers believe constitutes an overlooked factor in the survival of cultural works and artifacts. “It’s basically a distribution of manuscripts over works,” explained co-author Katarzyna Anna Kapitan, an Old Norse philologist at the University of Oxford, the University of Copenhagen, and the University of Iceland. “If you have a literary tradition that is even, it means that all literary works have more or less equal numbers of copies of manuscripts that preserve it. If it’s uneven, then you will have work that is preserved in a lot of manuscripts and then some works that are preserved in just one or two.” The latter works are less likely to survive.

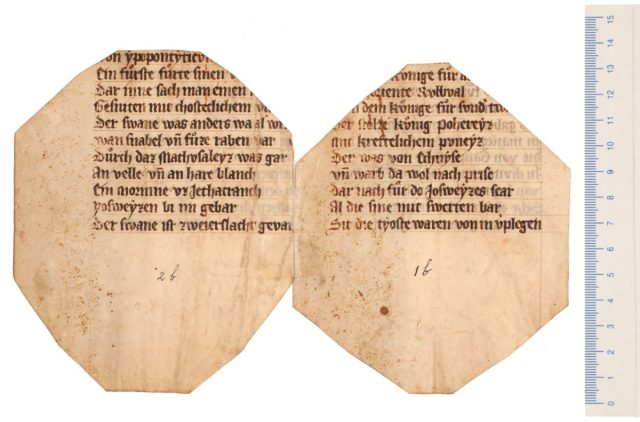

CC-BY University Library Antwerp

English medieval literature had a particularly high loss rate for works and manuscripts written in Old and Middle English, with just 7 percent of manuscripts surviving, amounting to the preservation of only 38 percent of chivalric and heroic works. “It might have something do with the different cultural status of English in that period,” co-author Daniel Sawyer of the University of Oxford explained, referring to the French-speaking Norman Conquest of England in 1066. “For a significant part of the Middle Ages, French was [one of] the more prestigious spoken language in England. I suspect books containing romances or heroic stories in English tended to be mid- or small-sized and less impressive and therefore more prone to being recycled.”