To quickly confirm an asymptomatic case of COVID-19, a second rapid test within an hour of a positive result can boost the accuracy of the result from 38 percent to 92 percent, according to a new study in JAMA Network Open.

The finding could guide future use of rapid tests for quick-turnaround decisions on interventions, as well as in situations where lab-based PCR testing is too costly or unavailable entirely.

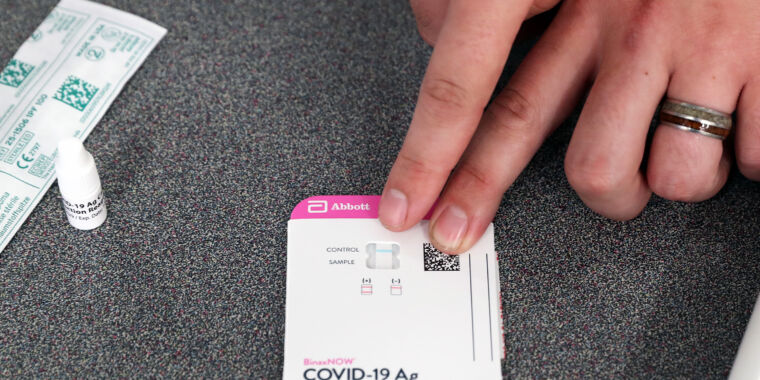

Currently, rapid tests are considered most accurate when used on people who are suspected of having COVID-19 and are within the first seven days of having COVID-19-related symptoms. For Abbot’s BinaxNow rapid test, for example, the test accurately identified infections in about 82 percent of symptomatic people (102/125 cases) and provided accurate negative results in about 98 percent of symptomatic people (227/231 cases).

The accuracy of rapid tests become fuzzier when testing people who don’t have any symptoms but have a known exposure. In these situations, many test makers advise users to take a series of tests, often 24 to 36 hours apart, to monitor if an infection develops over the course of a few days. Taking multiple tests has become particularly important amid the spread of omicron, with some reports that rapid tests may be slower to detect the start of those infections, even in the first few days of symptoms.

But the accuracy of rapid tests becomes even less certain when they’re used to screen asymptomatic people who may not have a known exposure to the infection. In these cases, the pretest probability of an infection is lower, raising the risks that any positive results are actually false positives.

Testing testing

To get a handle on how useful rapid tests are in this latter situation, researchers in New York dug into testing data from a workplace screening program. The researchers looked at rapid-test results only from asymptomatic people who were screened for COVID-19 between November 2020 and October 2021 and who used one of three rapid test kits (Sofia2 SARS Antigen Fluorescent Immunoassay, LumiraDx, or BinaxNow). In that time period, employees took 179,127 first-pass rapid tests. Of those, 623 were positive.

The 623 positive rapid tests where then confirmed with laboratory PCR testing, which is considered to be the gold standard for COVID-19 testing. The PCR tests found that only 238 of the 623 positives were truly positive—an accuracy rate of just 38 percent, meaning 62 percent were false positives.

But some of those 623 positive people—569 to be exact—also took a second rapid test within an hour of their positive rapid test. Of those 569 second-timers, 224 tested positive a second time, and PCR results agreed with that second test 92 percent of the time. That is, of the 224 people who tested positive twice on a rapid test, PCR results confirmed an infection in 207 of them.

That leaves the 345 people who tested positive on the first rapid tests and then negative on their second test. For this group, PCR results agreed with the second test—the negative one—95 percent of the time. That is, of the 345 who had a negative second test, PCR results also came back as negative for 328 of them.

The authors concluded that the overall accuracy of a second rapid test was 94 percent for people who at first tested positive. When the authors looked at accuracy over time, they noted that the estimate wasn’t consistent. The tests were most accurate when the virus was more prevalent. “As expected, test results appeared to be more accurate when community infection rates were higher and, therefore, the pretest probability was higher,” they wrote. But, “the diagnostic value of a second antigen test remained high regardless of pretest probability. As employers consider the best use of onsite or at-home rapid antigen testing, a second antigen test may be useful for more accurate diagnosis of COVID-19 infection and for guiding intervention,” they concluded.