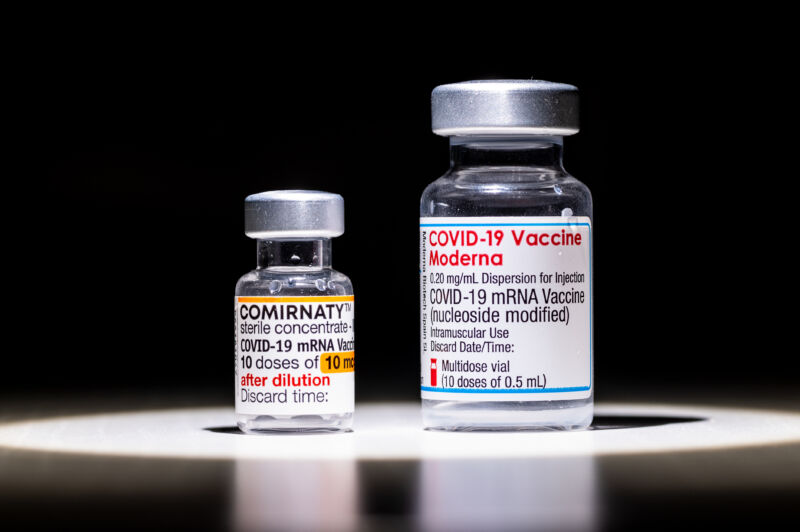

People ages 60 and older who were initially vaccinated with two Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine doses were better protected from the omicron coronavirus variant after being boosted with a Moderna vaccine rather than another dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

Those results are according to interim data from a small but randomized controlled clinical trial in Singapore and published this week in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases.

The study—involving 98 healthy adults—can’t determine if the Moderna booster is simply superior to a Pfizer-BioNTech booster for older adults or if a mix-and-match booster strategy is inherently better. It also focused solely on antibody levels, which may or may not translate to significant differences in infection rates and other clinical differences. It also only followed people for 28 days after a booster, so it’s unclear if the Moderna booster’s edge will hold up over time.

Still, the authors of the study, led by Barnaby Young of Singapore’s National Centre for Infectious Diseases, report that the beneficial effect seen by swapping from Pfizer-BioNTech to Moderna was significant enough that they don’t expect it to vanish with more participants. It also follows other studies that have suggested that mix-and-match boosting—aka heterologous boosting—can generate slightly different antibodies and reduce the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infections in people 60 and older.

For the new study, Young and colleagues looked at antibody levels in adults of all ages who had received two Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine doses between six and nine months before receiving a booster dose. The researchers excluded people from the trial if they had compromised immune systems or had evidence of prior SARS-CoV-2 infections (the presence of anti-N antibodies).

Of the 98 participants, 50 went on to get another Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine dose for their booster (homologous booster), while the remaining 48 received a Moderna booster (heterologous booster). The authors looked at their resulting antibody responses on the day of their booster, seven days later, and 28 days later. Specifically, they compared total levels of antibodies that targeted a key part of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, called the receptor-binding domain. They also looked at levels of neutralizing antibodies against a range of specific SARS-CoV-2 variants, from the ancestral strain to alpha, beta, delta, and omicron.

Slightly bigger boost

Overall, the heterologous-boosted group had slightly higher total antibody levels than the homologous group—about 40 percent higher on day seven and 30 percent higher on day 28, though the confidence intervals overlapped. But, when the authors broke out the groups by age, they found that the benefit was entirely from differences in the 60-and-up group. Antibody levels were equivalent among younger participants, regardless of booster type.

Among those 60 and older, there were 24 homologous-boosted participants and 23 heterologous-boosted participants. At seven days after the booster, the heterologous-boosted participants had two-fold higher antibody levels than the homologous group and 60 percent higher levels at 28 days.

Older heterologous-boosted participants also had higher levels of neutralizing antibodies against all of the SARS-CoV-2 variants tested—with the largest difference seen against omicron, which is notorious for thwarting vaccine-derived immune responses. At seven days, the level of neutralizing antibody inhibition was 89 percent in the heterologous-boosted group compared with 64 percent in the homologous-boosted group. At 28 days, the spread was 84 percent in the heterologous-boosted group to 73 percent in the homologous-boosted group.

Overall, Young and co-authors concluded: “For the vulnerable older age group in particular, a heterologous booster COVID-19 vaccine regimen induces a higher anti-spike antibody titer and a stronger neutralizing antibody response against the highly infectious Omicron variant (~20 percent higher neutralization) than a homologous booster regimen.”

The trial is still ongoing, so the authors will continue to add participants and data. They intend to reassess antibody responses in all participants at six months and 12 months after the booster. They will add people to the study who initially received Moderna vaccines to see if switching to the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for the booster offers a similar benefit.