A.G. Nerlich et al., 2022

There’s rarely time to write about every cool science-y story that comes our way. So this year, we’re once again running a special Twelve Days of Christmas series of posts, highlighting one science story that fell through the cracks in 2022, each day from December 25 through January 5. Today: Scientists conducted a “virtual autopsy” of a mummified toddler from the 17th century, concluding the remains are likely those of one Reichard Wilhelm (1625-1626).

A multidisciplinary team of Austrian and German scientists performed a “virtual autopsy” of the 17th century mummified remains of an infant, remarkably preserved in an aristocratic family crypt. They found that despite the infant’s noble upbringing, the child suffered from extreme nutritional deficiency, causing rickets or scurvy, and likely died after contracting pneumonia, according to an October paper published in the journal Frontiers in Medicine.

“This is only one case,” said co-author Andreas Nerlich of the Academic Clinic Munich-Bogenhausen. “But as we know that the early infant death rates generally were very high at that time, our observations may have considerable impact in the overall life reconstruction of infants even in higher social classes.”

According to Nerlich and his co-authors, there have only been isolated case reports on infant mummies, mostly from places with a cultural history of either embalming or serendipitous mummification—like ancient Egypt or South America—since infant remains tend to decompose rapidly under typical burial conditions. There is scant information on the life conditions, disease, and mortality in infant human remains from European cultural periods. Rare surviving specimens from crypt burials can thus provide useful insight.

The toddler mummy was interred in a family crypt in Hellmonsödt, Austria, belonging to one of the country’s oldest aristocratic families: the Counts of Starhemberg. The crypt is near the family residence at Wildberg castle, and this was the only infant interred there, housed in a small wooden coffin with no identifying inscriptions. (Adult members of the Starhemberg family were interred in intricately decorated metal coffins with inscriptions.)

-

The infant mummy of the Hellmonsödt crypt in Austria, clad in a silk coat.

A.G. Nerlich et al., 2022 -

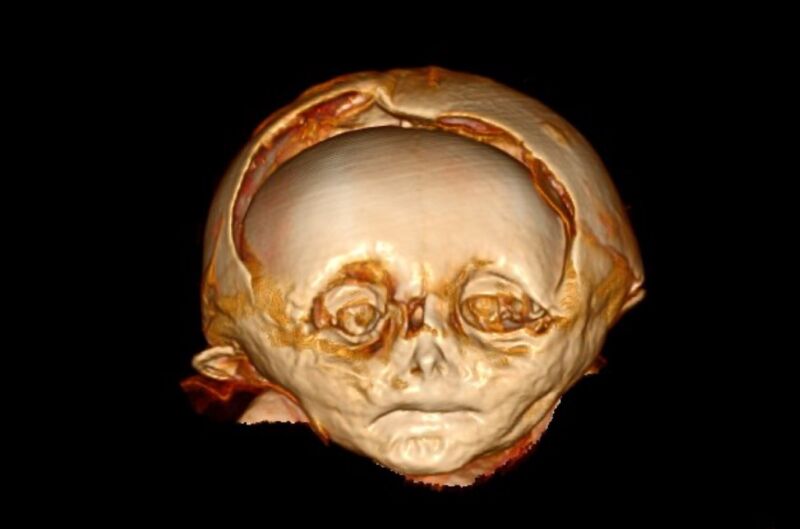

Detail of the infant mummy’s face.

A.G. Nerlich et al., 2022 -

Detail of the mummy’s left hand on the abdomen. Note the retracted navel.

https://capture.dropbox.com/hnRUx1H7xsOuSkyO -

CT scan of the full body produced a 3D reconstruction of the skeleton.

A.G. Nerlich et al., 2022 -

The CT scan showed evidence of “rickety rosary” or “scurvy rosary.”

A.G. Nerlich et al., 2022 -

CT scan of the skull base.

A.G. Nerlich et al., 2022 -

Axial CT sections through the thighs revealed a subcutaneous fat tissue envelope

A.G. Nerlich et al., 2022 -

Axial CT sections through the chest showed remnants of lung tissue with pleural adhesions.

A.G. Nerlich et al., 2022

While the crypt was undergoing restoration work, the infant’s coffin was opened for examination. The body was wrapped in a well-preserved long silk coat with a hood that covered the skull, and the quality of the silk indicated high social status. Much of the skin was also well-preserved, including the male genitalia.

To learn more, the remains were subjected to a whole-body CT scan, enabling Nelrich et al. to create 3D reconstructions of the body, particularly the skull. The femur, tibia, and humerus reconstructions enabled them to calculate the bone length. They also took a biopsy of the soft tissue from the lower lumbar region for radiocarbon dating and histological analysis, revealing the child was about a year old when he died.

As for the child’s identity, the Starhemberg family crypt was reserved for titled members—usually firstborn sons—and their wives. So the infant boy must have been the firstborn son of one of the counts. He was likely buried sometime between 1550 and 1635 CE, and Nerlich et al. used historical records to narrow the range further to after the crypt was renovated around 1600 CE. They concluded that the mummified infant remains were most likely those of Reichard Wilhelm, firstborn son of Erasmus der Jungere.

There was considerable inflammation of the lungs, consistent with pneumonia. The team also noted malformation of the ribs in a pattern consistent with severe rickets or scurvy. So even though there was evidence—in the form of subcutaneous fat tissue around the thighs—that the child had been overweight (aristocratic children would have been well-fed), he was also likely malnourished with a severe Vitamin D deficiency, making him more vulnerable to pneumonia.

“The combination of obesity along with a severe vitamin-deficiency can only be explained by a generally ‘good’ nutritional status along with an almost complete lack of sunlight exposure,” said Nerlich. As a result, “We have to reconsider the living conditions of high aristocratic infants of previous populations.”

DOI: Frontiers in Medicine, 2022. 10.3389/fmed.2022.979670 (About DOIs).