Every year, an estimated 13 million people go whale-watching around the world, marveling at the sight of the largest animals ever to inhabit Earth. It’s a dramatic reversal from a century ago, when few people ever saw a living whale. The creatures are still recovering from massive industrial-scale hunting that nearly wiped out several species in the 20th century.

The history of whaling shows how humans have wreaked careless havoc on the ocean, but also how they can change course. In my new book, Red Leviathan: The Secret History of Soviet Whaling, I describe how the Soviet Union was central both to this deadly industry and to scientific research that helps us understand whales’ recovery.

A humpback whale breaches in Boston Harbor on August 2, 2022. Whaling greatly reduced humpback whale numbers, but the species is recovering under international protection.

From wood to steel and bad to worse

At the start of the 20th century, it seemed whales might gain a reprieve after years of hunting. The era of whaling from sailboats, depicted in such memorable detail by Herman Melville in Moby-Dick, had nearly wiped out slow, fat species like right and bowhead whales and also wreaked substantial harm to sperm whales.

In the 1800s, US whalers sailed without restraint or hindrance into every corner of the world’s oceans, including waters around Russia’s Siberian empire. There, tsarist officials watched in helpless rage as Americans slaughtered whales upon which many of the region’s Indigenous peoples relied.

In the 1870s, petroleum began to replace whale oil as a fuel. With few catchable whales remaining, the industry appeared to be near its end. But whalers found new markets. Through hydrogenation – a chemical process that can be used to turn liquid oils into solid or semi-solid fats – manufacturers were able to transform smelly whale products into odorless margarine for human consumption.

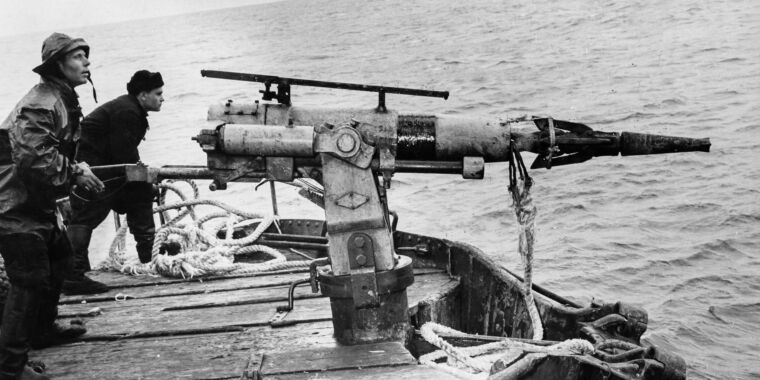

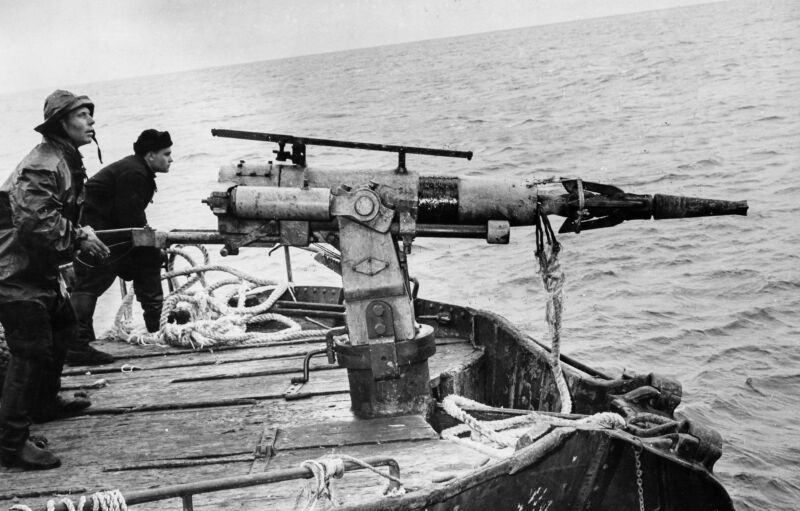

Around the same time, Norwegians invented the explosive harpoon, which killed whales more efficiently than hand-thrown versions, and the stern slipway, which allowed whale carcasses to be processed on board ships. Along with diesel engines and steel hulls, these technologies enabled whalers to target previously untouched species in once-inaccessible locations, such as the Antarctic.

Late to the party, late to leave

As mechanized whaling gained force in the 1920s and ‘30s, Norwegian, British, and Japanese whalers cut through populations of blue, fin, and humpback whales on a scale that is hard to believe today. In what scientists once thought was the peak catch year, 1937, over 63,000 large whales were killed and processed.

World War II briefly suspended this slaughter, which many governments were starting to realize threatened the survival of some whale species. In 1946, whalers, statesmen and scientists created the International Whaling Commission in hopes of heading off a return to disastrous prewar levels of whaling.

That same year, the USSR joined the IWC and took control over a former Nazi whaleship, which it renamed the Slava, or Glory. No one suspected the central role the country would play in the most disastrous two decades of whales’ long history on Earth.