NASA

NASA confirmed this week that its Lucy mission to explore a series of asteroids has a clean bill of health as it approaches a key gravity assist maneuver in October.

In a new update, the space agency said Lucy’s solar arrays are “stable enough” for the $1 billion spacecraft to carry out its science operations over the coming years as it visits a main-belt asteroid, 52246 Donaldjohanson, and subsequently flies by eight Trojan asteroids that share Jupiter’s orbit around the Sun.

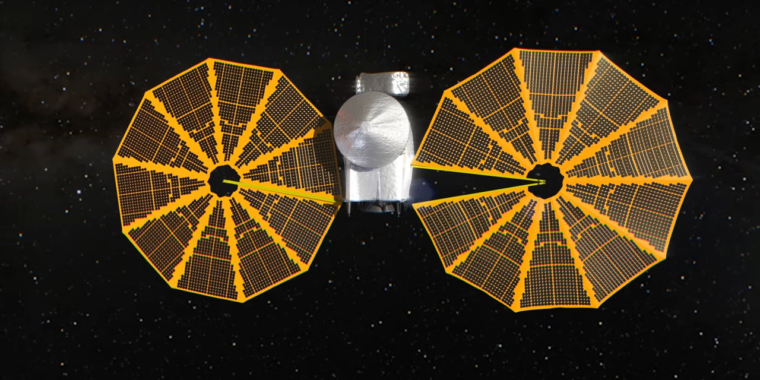

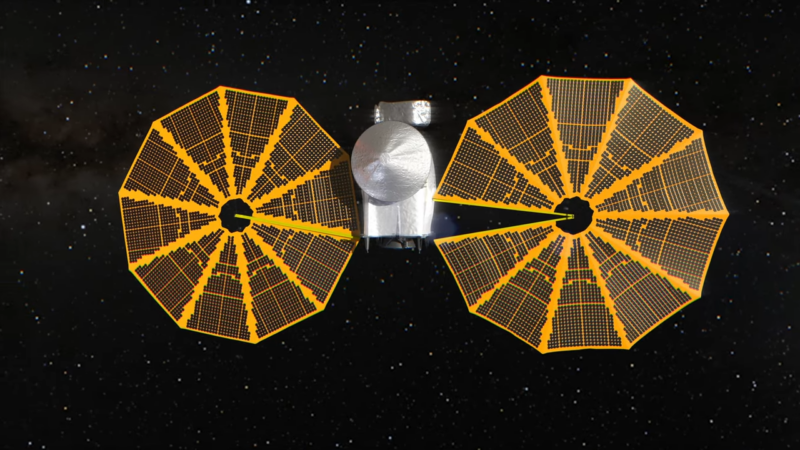

The fate of the Lucy mission had been in question since the first hours after it launched on an Atlas V rocket last October when one of its two large solar arrays failed to fully open and securely latch. Each of the arrays was intended to unfurl like a hand fan.

Scientists and engineers from the space agency and its mission contractors, including spacecraft builder Lockheed Martin and solar array designer Northrop Grumman, huddled within hours of the launch. In those initial meetings, they had “intense” conversations about the fate of the mission. At the time, the engineers were not certain why the solar array had failed to open because Lucy’s cameras cannot be pointed toward the solar arrays.

So during those early meetings, the scientists and engineers debated whether the solar array problem could be fixed and whether the mission could complete its ambitious scientific observations without two fully operational solar arrays. The partially closed array was generating about 90 percent of its expected power.

Eventually, after months of analysis, testing, and troubleshooting, the team realized that the lanyard designed to pull the solar array open had gotten jammed. Lucy is equipped with both a primary and backup motor to deploy the solar arrays, but they were not designed to be fired in tandem. This spring, the engineers decided the best course was to fire both the primary and backup deployment motors for the solar array simultaneously in hopes that this additional force would unstick the lanyard.

So from May 6 to June 16, on seven different occasions, engineers commanded the deployment motors to power on, and these efforts helped. Out of a full 360 degrees, NASA says the solar array is now between 353 and 357 degrees open. And while it is not fully latched, it is now under sufficient tension to operate as needed during the mission.

With the solar array issue apparently solved, mission operators can turn their focus to an Earth flyby in October when Lucy will pick up a gravity assist—the first of three en route to the main asteroid belt. As part of this fuel-efficient trajectory, Lucy will fly by its first target in April 2025, the main-belt asteroid named after Donald Johanson, the American anthropologist who co-discovered the famed “Lucy” fossil in 1974. The fossil, of a female hominin species that lived about 3.2 million years ago, supported the evolutionary idea that bipedalism preceded an increase in brain size.

The Lucy asteroid mission, in turn, takes its name from the famed fossil. By subsequently visiting eight Trojan asteroids, scientists expect to glean information about the building blocks of the Solar System and better understand the nature of its planets today.

No probe has flown by these smallish Trojan asteroids, which are clustered at stable Lagrange points trailing and ahead of Jupiter’s orbit 5.2 astronomical units from the Sun. The asteroids are mostly dark but may be covered with tholins, which are organic compounds that could provide raw materials for the basic chemicals of life.